To burnish or not to burnish?

To burnish or not to burnish?

When it comes to burnishing concrete, It all depends on the look you’re after

For many years, burnishing concrete was common to make commercial floors harder, more durable and easier to clean. But these floors had no aesthetic value. They didn’t need to; they were an underlayment.

“In the old days, they burnished concrete for structural value,” agrees Tom Ralston. Ralston is the president of Tom Ralston Concrete, a third-generation concrete company in Santa Cruz, California. “The more you trowel concrete, the harder and the more abrasive-resistant it becomes.”

But in addition to this incredible hardness, something else happens to the surface’s appearance, says Ralston, a frequent speaker and trainer of decorative concrete techniques at industry gatherings. “We found that burnishing really mimics acid staining in that it creates a kind of patina-like variegation that people are looking for these days.” He recalls one client who wanted a variegated-looking countertop some years back. With the help of a spray bottle, “We found we got a nice variegation with gray natural concrete just by adding water.” The more they burnished — with a burn trowel typically three inches wide — the more variation of color they got.

Ralston, who is always scouting for new products and techniques to help him with his one-of-a-kind creations, was definitely onto something that went beyond the basic burnishing concrete of yore.

The highs and the lows

When you trowel over and over again-which is what burnishing concrete is – it makes for a shiny, smooth and hard surface, a look that people today want for their interior floors and countertops.

Rather than for the shine, Ralston says he burnishes to get the “highlights and lowlights” of naturally colored concrete or color applied to the concrete via a hardener. “If you extend the concept of burnishing to include color hardeners that allows you to open up a whole array of visual possibilities.Your trowel then becomes similar to that of an artist’s brush. You could make colored concrete look like an oil painting.”

And cutting-edge contractors like Ralston are finding out that if you flash in color as you employ these burnishing concrete techniques you can create masterpieces.

It’s all in the blend

When you hard trowel colors together, you’re actually blending them for a more natural look, Ralston says. “Look at a piece of natural slate, stone or bark and you’ll see a subtle blending of colors. That’s what you’re trying to accomplish with your trowel. You’re burnishing for the visual effect, not to create a scratch-resistant surface or a surface that cleans easier.”

The more you trowel, the more mottled the coloring appears — which isn’t always a good thing. When you overtrowel integrally colored concrete you may end up giving clients a mottled effect rather than the color-consistent surface they wanted. And if you really overtrowel hard concrete — and this is especially true with power trowels — the aluminum in the mix and the steel in the blades can get so hot it will burn and blacken.

Going through the steps

Alan Bouknight, owner of Azzarone Contracting in Minneola, New York, has been burnishing concrete for nearly 10 years. In the last year, he says, his company has made a “quantum leap” in perfecting the process, thanks in part to new tools, new techniques and being smart enough to learn from mistakes. “We’re willing to see how far we can push the limits of concrete,” he says. “It has an inherent beauty if you know how to coax it out.”

For a burnished finish — “The right terminology is a hard-steel-trowel burnished finish” — first strike the surface with a straightedge to make sure it’s fairly level, pass with a bull float and, when the concrete is ready, come in with a machine and hit it once or twice with shoes or pans to flatten it, says Bouknight. The drag from the oversized shoes works the fines and the cream to the surface while the vibration of the machine shakes the mixture and the heavier aggregates sink. The oversized shoes help to distribute the material and fill in the hills and valleys.

Next, remove the shoes and go over the surface with your stainless steel finish blades to help create a polished finish. During each stage, the concrete keeps getting harder and harder and you must determine when — and if — to get on it again. Each time you machine trowel, you need to increase the speed and pitch of the blade, Bouknight says, because you’re building up friction and heat with the drag and that can help burn the floor.

A pattern is also important. “You need to go in different directions so you won’t get waves in the floor; you want it to stay flat. Typically, you make passes like north to south and then east to west to give you nice coverage between coats. It’s a lot like painting,” says the seasoned contractor.

The method he just described, he says, will produce a burnished — almost marbleized metallic-look to the floor.

Burn, baby, burn

Bouknight remembers when the standard for finishing concrete floors was to give the client a burnt floor. During his boyhood, he recalls accompanying his father or grandfather to job sites in New York City some evenings and “You could see sparks fly off the blades. That’s how many times they’d trowel it.” Burnt floors are hard as steel, he explains, and it didn’t matter if they were blackened. “The floors were going to be covered up with carpet or linoleum anyway.”

Today, “We don’t have to burn the floor as much because we have plenty of additives to make it strong. We can avoid the burn and get a beautiful opulence. Each time you make a pass, you’re layering the burnish marks, which gives a sense of depth to the floor. It may look rough or coarse, but it feels like hard silk.”

Slight of hand

Bob Harris, former director of product training for the Scofield Institute, the educational arm of L.M. Scofield Co. in Douglasville, Georgia, explains that when burnishing involves a hand trowel: “With each successive pass, you use a smaller tool. The smaller the trowel the more weight you can apply to densify the surface. You’d start with, say, a 20-inch trowel then a 12 then an 8-inch burnishing trowel. That’s probably as small as you’d typically go. Obviously, this method wouldn’t be practical for large jobs.”

When you burnish, you’re making the surface slick and very smooth, as well as altering the color. “Burnishing creates a very nonuniform look, kind of a marbleized appearance where the color darkens in certain areas,” Harris says. “Some people call it a ghosting effect.”

If you’re selling this look, it can be very attractive. However, if someone wants a monochromatic surface it’s not the way to go.

Bob Ware, president of the Decorative Concrete Store in Cincinnati, agrees with Harris’ advice. He cautions contractors to be careful with integral colors. “The term burnishing, in essence, means burning the finish. Trowel machining colored concrete is a careful process. It may only require one to two passes.”

If you do more, instead of a high gloss, “you’ll end up with streaks marks — or worse, black marks — from the trowel machine, tinting the true color you really want.” So the final pass of many colored concrete floors is hand troweled by a crew on kneeboards.

To be on the safe side, a preconstruction meeting should be arranged between the finisher and the architect to decide on the look of the floor. If the job is large enough, Ware urges, pour an 8-by-8 foot mock up for the architect’s approval.

Take care

To be successful time and time again, Bouknight — whose mantra is “perfection, not production” — notes it’s very important to find a ready mix supplier who’s cognizant of what you want to achieve and is involved in helping you achieve it. “When we create a floor that’s stunning, I call the supplier and tell them they must see for themselves what we can do with these materials,” he says.

“The color chosen limits the degree of how much you can burnish the floor,” Bouknight says. Each trowel pass darkens the floor. Thus, if the floor is, for instance, a really light beige color you can burnish it in a subtle way. However, you’ll have to sacrifice a really tight and smooth finish or you may wind up burning the cement in places. “The more you trowel, the more radical the background color becomes. You really have to pay attention and make sure you don’t overtrowel. Typically, light integral colors don’t work well,” he says. “Reds work well if you’re careful.”

Bouknight says he always uses a machine to burnish floors. Depending on the application, these machines can weigh anywhere from 50 to 200 pounds and can be fitted with different shoes and blades. “A guy with a hand trowel can get a smooth surface but it will look monochromatic,” he says. “You won’t get the subtle, variegated, marbleized look that you get with a machine.”

Sound concrete finishing practices and using the right tools make all the difference, says Bouknight. He recommends having your machines serviced at least three times a year and to make sure everything is balanced. “Maintenance and cleanliness of equipment is very important to a successful job,” he stresses.

Machinery on the horizon

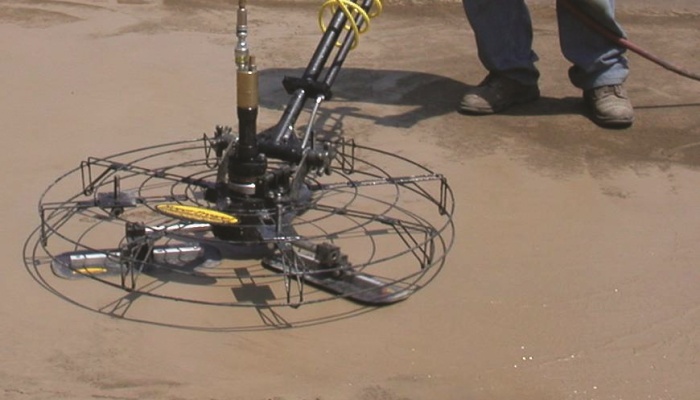

Matt Casto is the vice president of technical services for Bomanite Corp. in California. He says the mottled look has become more prevalent with the introduction of polymer-modified micro-toppings. “The thinness of the material has made it very cost effective to blend colors together,” he says. “You can put down two to three colors quickly and mottle them together by dragging them on, brushing them on or spraying them on.” And now there’s another option: you can “HoverTrowel” them.

Makers of HoverTrowel, a pneumatic-driven power trowel initially developed to finish decorative aggregate epoxy floors, are working with a number of manufacturers to establish a niche in this market with accessories and modifications designed specifically for overlayments. Industry experts are experimenting with various RPM and torque-load motors with weights. They are working to determine the optimum method and timing for these polymer-modified applications.

According to Drew Fagley, president of HoverTrowel Inc., this power trowel can be used in lieu of hand troweling. On occasion, it can also be used in place of conventional trowels. “The resulting finish is consistently uniform and flat,” he says.

Fagley sees the machine as a big plus when hard troweling multiple colors into a surface. Conventional power trowels are too heavy for some surfaces. The also may not achieve the desired effect, he says, so crews currently finish the job by hand. It’s in these instances that the lightweight HoverTrowel is finding success. The machine can be used effectively to hard trowel in colors, thus reducing manpower and finishing time. “Instead of six guys going out with kneeboards, we can outfit an operator and a support man with float shoes we call slides — which are basically kneeboards for your feet.”

Various types of motors are available to supply different torque loads for the more resin rich systems as well as today’s newer polymer toppings. You can add additional weight, in 2 pound increments up to 22 pounds, to further fine tune the trowel’s performance.

In addition to the standard tool — steel blades, stainless-steel and composite blades are available — as well as various float blades made of mahogany, magnesium, aluminum or laminated resin-to eliminate unsightly burnishing marks and to produce various finishes.

“About the only thing you can’t change about the HoverTrowel are the results,” Fagley says with a laugh. It has an extension handle that doubles its length in six-inch increments. Two different diameter guards are available to complement the multiple blade and float sizes. And soon a four-cycle retrofit motor will be on the market.

“We’ve played around with the HoverTrowel. I believe that it’s going to be a good tool to burnish micro toppings with,” says Bomanite’s Casto. “It’s lightweight and has the ability to get onto that material quickly.”