What is ground and polished concrete? How do we determine the difference between a topical-polished floor, in which a product has been applied to the floor to seal it, and a mechanical polish with bonded abrasives?

For several years it seemed that the term “polished concrete” was used indiscriminately. One of the bigger problems that arose was “how to specify a polished concrete finish.” An architect or designer could simply use the term and expect a result, but that result might not exactly match the design intent or the owner’s expectation.

How can a specification clearly state the overall criteria needed to reach an acceptable level? Combine key measurements with specific design benchmarks.

For example, the design criteria may include a level of cut or aggregate exposure, a specific color, and logos or other design elements. The key measurements should include properties for surface refinement such as:

- Gloss level (as discussed in ASTM D523)

- DOI (distinction of image, discussed in ASTM D4039)

- Abrasion resistance (discussed in ASTM C944)

- SCOF (slip coefficient of friction, discussed in ANSI B101)

Understand that a true ground and polished finish is achieved through a combination of mechanical grinding, honing and polishing, combined with chemical densification and treatments to produce a properly refined surface that is light-reflective, durable and easy to maintain. If we begin with the end in mind, the logical steps to completion make sense and are easy to follow.

Traveling as I do, I speak with polishing contractors all over the nation, and a common point of contention is how many steps people are taking on any given floor. Simply put, fewer steps equals lower cost. When estimating projects, we are finding large discrepancies in the bids because everyone is bidding something different. Specifiers need more education and understanding of the methods used to achieve a quality floor so they can weed out low-cost processes that will not produce a durable floor or surface.

The Concrete Polishing Association of America has put forth true definitions for polished surfaces that help clear the air here. Their definitions include:

- Bonded Abrasive Polish (a true ground and polished process)

- Burnished Polished Concrete

- Topical Polished Concrete

Each of these processes has a place in the industry, but only with a closer look can the specifiers see the true difference in durability and life-cycle costs associated with these floors.

One way to make specifications more clear is to add sections for the four key measurements listed earlier in this article. Each of these provides specific data that can be confirmed through testing, and they work with the design elements to produce a clear vision of the intended or desired result.

The measurements up close

The measurements up close

The three most common or reliable measurements would be DOI (distinction of image), level of gloss (specular reflection), and slip coefficient of friction.

With DOI, we get a number that helps us quantify clarity in the surface or haze. Depending on the testing meter we use, we get a number from 1 to 10 that indicates how much clarity there is in the surface. A 10 would be perfect clarity (mirror) and 1 would be a hazy or cloudy finish.

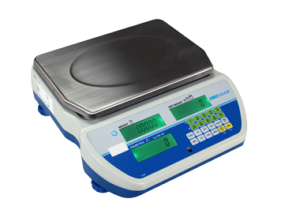

The next measurement to look at is the level of gloss, indicating the specular reflection of the surface. This is measured using a digital gloss meter, which measures the bounce of light at a 60-degree angle from the surface. Aggregate exposure will affect the gloss reading, but note that this test averages results together to deliver an overall number.

When specifying for haze or gloss, a range should always be given and not a specific number. Usually this will read low, medium or high gloss depending on the project requirements. The CPAA specifies four levels of cut (determining aggregate exposure) and four levels of gloss. Most manufacturers specify three levels of each for simplicity.

The third measurement to specify is the slip coefficient of friction. These numbers will vary depending on the surface being tested and type of equipment used, but they generally provide the owner with results that describe the safety of the surface with regard to slip-and-fall conditions. ANSI B101 is the most commonly followed specification for this, but there’s also ASTM C1028, which is a test method for determining coefficient of friction for any type of finished flooring.

The third measurement to specify is the slip coefficient of friction. These numbers will vary depending on the surface being tested and type of equipment used, but they generally provide the owner with results that describe the safety of the surface with regard to slip-and-fall conditions. ANSI B101 is the most commonly followed specification for this, but there’s also ASTM C1028, which is a test method for determining coefficient of friction for any type of finished flooring.

When measuring, I have had good luck using the ASM-825 slip meter, which is a static pull meter from American Slip Meter Inc., but recently we’re seeing the RSI BOT-3000 digital tribometer (dynamic slip co-efficient) being specified.

Some contractors own the required testing equipment, but most have a testing lab perform the tests for liability reasons. The BOT-3000 is a very expensive piece of equipment to own. However, a digital gloss meter is relatively inexpensive, ranging from $600 to $1,500.

Another nice unit to own is a combination unit that reads gloss and haze together. These cost slightly more but certainly give you good information. This unit can be useful to a contractor who wants to check his performance criteria as he is processing the floor. He can document his own results even before the owner has any testing done.

In many cases the owner may not require any additional testing other than a slip coefficient test. When turning a polished concrete project over to the owner, it is good practice to include a turnover document that lists specified and actual key measurements of your job. This document can also help provide maintenance recommendations for the owner as well.

Understanding and performing key measurements is a great way to specify, produce and document high-quality ground and polished floors. If you’re not already doing this for your customers, you should look into learning more about it so you can set yourself and your company apart from the others. It’s also a great way to sell yourself and your process at the front end of a project. This sends the message to the project team that you’re an educated and experienced company that produces high-quality floors.