When a contractor decides to apply a release agent to a wet concrete surface to keep it from sticking to a stamp, there are two ways to go: liquid or powder. Each has advantages, but each also causes problems.

Contractors who use powder release must wash it off afterward, while liquid evaporates on its own, an extremely handy feature to consider when stamping indoors or near a pool. But powder release agents are the only ones that come with color. Liquid release agents are colorless.

So, for a decorative concrete contractor, the choice can be a tough one.

Powder puff

Powder or ‘cast-on” release agents have the consistency of baby powder, which allows them to resist both wet concrete and rubber stamp but gives them the tendency to get all over everything else.

They’re typically made with paraffin, which resists adhesion to many surfaces. The fine grit of the powder repels water, as well as damp concrete. Powders are typically colored, but can also be white, which leaves no tint behind after the release is washed away.

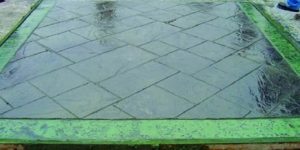

When a stamp presses into a layer of powder release, the powder will be pressed most heavily into the edges of joints, cracks and pattern lines, thereby creating shading. The paraffin-based particles carry particles of dye, which are absorbed by the moisture in the concrete, explains George Lacker, owner of GLC3 Concrete, a contracting firm based in Plantation, Fla. After the paraffin material is hosed off, the dye remains. ‘It’s pretty much like staining it,” Lacker says.

Applying two or three levels of powder release on top of each other before stamping creates all sorts of possibilities for natural-looking effects, such as the multicolored look of natural stone. ‘It leaves a lot of colors and mottling that looks fairly natural,” says Clark Branum, technical director at Brickform Products. ‘When washing off powder, contractors can control how much of each color to take and leave.”

According to Steve Johnson, marketing and product development, ready-mix division, for Solomon Colors, powder has no equal in the multicolor effects department. ‘Powder release is the fastest method to get multiple colors,” he says.

But powder releases are also messy. Hanging clouds of the fine dust will settle in nostrils and on clothes, walls and furniture. And washing it off a stamping project that is indoors, abutting a pool or near an environmentally sensitive area is pretty close to impossible.

If using a liquid release agent, a contractor can see a newly stamped texture right away, fixing it if necessary. Powder must be cleaned off before the contractor knows anything, says decorative concrete contractor Richard Smith of West Hills, Calif. ‘With a liquid release, you spray it down and see what you get. With powder, it’s hard to tell until you wash the release agent off.”

That can pose particular problems on a big project, Smith says, in which a harried laborer may inadequately pepper a 4-square-foot section and not realize it until too late. ‘There’s no way of seeing it.”

Powder can also give a false impression of dryness because it floats on top of the slab, Smith says.

The decision to go with liquid or powder will also be affected by location and climate, Smith notes. Different parts of the country have access to different base elements — fly ash in California, for example — that will affect both the makeup of the concrete and the availability of powders to pitch onto it. If the weather calls for wind, a powder stamp project will get even dustier.

Powder release does allow a contractor to get onto a slab to stamp a little sooner because it dries out moisture, says Lacker of GLC3. On the other hand, liquid release creates a membrane that helps concrete hold its set a little by slowing the evaporation of water.

Lacker adds that these days, great-looking two-color jobs can be completed without the mess of any powders. ‘I would just stamp with liquid, then tape the slab off and spray it afterward,” he says. ‘I would use acid stain, tints and dyes. It all depends on what I was trying to achieve. We’ve come a long way.”

Liquid assets

Liquid release was initially designed for stamping overlays indoors, where rinsing the surface clean is impractical, says Branum. ‘I think this is probably one of the biggest applications of it.”

Some are called ‘bubblegum releases,” because chemicals have been added to give the liquid releases a bubblegum smell, masking the smell of solvent in malls and casinos. In general, liquid releases cost more than powders.

Liquids present some unique factors to consider during the application process. For one thing, a contractor may want to wait for a moment between applying the release agent and placing the stamp, Johnson says. ‘Spray it on and let it sit for a minute or two. Let the carrier evaporate a little bit.” After a short time, the initial fumes dissipate, while an oily residue stays to aid the stamping process.

However, wet is still wet. When texture tools are pulled away from a surface coated with an oily release, suction could pull on the wet concrete, leaving spotting and blotches, Branum says.

Liquid agents can also become troublesome on driveways or other sloped surfaces, Branum says. Liquid release is slippery by nature, and it will streak and stream off a slanted surface.

When an indoor job calls for a liquid and a color, one popular move is to simply mix powder release into liquid release and spray the mixture. ‘Spray a little more over the top after you pull the stamp up,” Smith adds.

Mixing the two is pretty common, Branum says. ‘Adding powder to liquid is one way to speed up the highlighting process. But it’s an advanced process. It requires a lot of practice and touch.”

Infused liquid distributes less colored powder than a hand or brush will. The color will also flow into cracks differently. Powder release on its own is pressure-sensitive material, Johnson explains. ‘The stamp is going to force that release agent into the surface of the concrete. If you put even more pressure on the concrete, more sticks to it.”

Liquid releases, in contrast, don’t rely on pressure to place and distribute infused color. The mixed-in powder seeps into the cracks and crannies of the freshly stamped texture instead of dusting the top, and the deeper, the darker. If more color is needed, more infused liquid can be spritzed on afterward. ‘They are relying on gravity and evaporation,” Johnson says.

He agrees that it’s not easy to get it right. Inexperienced contractors might overlap dark areas, or spray too heavily, or simply botch the mixing process. ‘That’s the garage chemistry that’s coming in,” he says. ‘There’s a lot of practice that needs to be done to get that to look right.”

The busy contractor might not have the time, labor, know-how or patience to pull this off quickly, Johnson says. ‘Artists eat this stuff up. But guys on the fast track, who pour three or four times a day to keep up with business, they don’t want to experiment.”

Getting the job done

While throwing powdered release is the most obvious way to get it out over a slab, that method can leave streak marks, according to contractor Richard Smith. One old-school way is to roll the powder over concrete with large paint rollers, he says.

Johnson of Solomon Colors recommends using a whip brush or thick paintbrush to throw powder release on a vertical surface. ‘You can control how much you put on with that kind of brush,” he says. ‘You just need a dusting on there.”

Then there’s the bigger problem with powder: How to get it off?

‘Most guys for years have used a pressure washer,” says Branum of Brickform. ‘I don’t recommend this method. You run the risk of delaminating color hardener if you get too aggressive with pressure washers too early, especially in cold climates.”

Instead, Branum suggests using a low-pressure hose with a nozzle to make a sweep over the surface. Release can also be removed by dispersing a solution with some kind of cleaning agent: a light muriatic solution, an efflorescence remover, or even dish soap. A cleaning agent and brush will cut release agent right off the surface, Branum says.

Brickform recommends gloves and respirators when applying its powder release agents. ‘With any stamping with colored release agents, you should mask all adjacent areas,” Branum says. ‘It’s like talcum powder. It’s that light. When you fling it with a brush, it’s going to linger, going to ‘poof.'”

Brickform recommends gloves and respirators when applying its powder release agents. ‘With any stamping with colored release agents, you should mask all adjacent areas,” Branum says. ‘It’s like talcum powder. It’s that light. When you fling it with a brush, it’s going to linger, going to ‘poof.'”

Lacker of GLC3 Concrete says he removes powder with a pressure washer or a light acid wash. Sometimes contractors, prodded by customers who like the tint of a coat of powder sitting on their slab, will simply try to lay sealer over the powder release agent without washing it off, he says. Inevitably, the layer of sealer delaminates. ‘People only try that one time.”

But Lacker also cleans up after a liquid release, using a degreaser to counteract the oily liquid, and for the same reason. ‘You can have the same problem with a sealer sticking,” he says. ‘If you’re going to put a water-based sealer on top of a liquid release, it’s a good idea to get it really clean.”

There are all kinds of things that contractors come up with to disperse powder, Lacker says, from brooms to dust bags. He likes to use ‘throw brushes,” old whitewash brushes with 4-inch hairs that are half the length of the tool. He’s done it by hand, but hands require gloves, and the finished result is more uneven. ‘It was so much better with the brush,” he says.

In terms of protection, Lacker says the most essential piece of gear is a respirator. ‘You’ve got to wear a respirator. You can’t breathe that stuff. It’s terrible.”

Liquid and powder release agents can be stored for a long time as long as they’re sealed tight in cool, dry space. But Smith doesn’t keep much. ‘Liquid release, we use it so much, there’s no storing. It does have a long shelf life but we typically don’t keep it. We blow through it so fast.”

His workers usually mix leftover powder into liquids, particularly powders that are blacks, browns and other earth tones. A release with an eccentric color such as ‘Venetian pink” will linger around the warehouse for one or two years, then get taken to the dump, he says.

Lacker says well-sealed materials will last as long as the shelf life on the packages. But ultimately, storage is a frustrating topic, he says. ‘The rule of thumb is that if you throw it out after the first week, you need it in about a month. If you save it, you throw it out after about a year, because you get tired of moving it around.”