After serving his obligatory stint in the military in the mid-’50s, Robert J. Harris studied engineering at Stockton College for two years. Pursuing a degree and supporting a developing family didn’t quite mesh, so he switched career paths — a move he has never regretted — and went on to complete a three-year apprenticeship in Oakland, becoming a bona fide union cement mason in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1960.

After serving his obligatory stint in the military in the mid-’50s, Robert J. Harris studied engineering at Stockton College for two years. Pursuing a degree and supporting a developing family didn’t quite mesh, so he switched career paths — a move he has never regretted — and went on to complete a three-year apprenticeship in Oakland, becoming a bona fide union cement mason in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1960.

From there, the journeyman worked his way up to foreman for various companies and then superintendent. By 1972, he had formed his own company, Harris and Harris, which largely focused on public works projects involving bridges, dams and freeways throughout the state of California. The Class A general engineering contractor also has been involved in myriad private endeavors, everything from skateboard parks and underground cemetery vaults to tilt-up concrete and entire commercial complexes.

Harris, who now lives in Northern California’s Brentwood, says his construction career goes way back. When he was 5 or 6 years old, his dad, Robert J. Harris Sr. — “who was a damn dam builder” — began to teach him how to operate heavy equipment. “Just like a farmer is out there with his kids on a tractor, when their legs are long enough to reach the pedals, he was teaching me what that lever was for, what this one did,” Harris recalls about his first outing to the Mojave Desert. “I became familiar with the jargon and technology at a very early age.”

When he was 13 years old, he joined the labor union and helped his father with a road project in Montana. “I was an independent child,” he says. “I loved running through the forest and going down rivers and exploring on my own. I wasn’t a loner — I had friends and all — I just liked doing things by myself. And I still enjoy my own company today,” as well as the company of his family. He and his wife, Mary Lou, have three children: Nancy, Lori and Bob.

When he was 13 years old, he joined the labor union and helped his father with a road project in Montana. “I was an independent child,” he says. “I loved running through the forest and going down rivers and exploring on my own. I wasn’t a loner — I had friends and all — I just liked doing things by myself. And I still enjoy my own company today,” as well as the company of his family. He and his wife, Mary Lou, have three children: Nancy, Lori and Bob.

When Harris’ son, Robert P., got old enough, he accompanied him on side jobs that he’d do on weekends. Harris says young Bob — who now is director of product training for the Scofield Institute, the educational arm of L.M. Scofield Co., in Douglasville, Georgia — used to carry stakes and lumber and help him build patios, backyard retaining walls and such whenever he could. From the time his son was a teenager into his young adult years, they often worked together on various projects.

The one thing the younger Harris says sticks out in his mind during these formative years was how hard it was being the boss’ son. “It was 10 times more difficult than what it was for the average employee,” he says. His dad expected (and still expects) perfection and always pushed him to do his best. Although he concedes it took him years to appreciate his father’s drive (“I just thought he was kind of cantankerous at the time”), he’s thankful his dad taught him to take pride in his work and to be proud of his trade and the industry as a whole.

All three Robert Harrises have been marked by this “driven” trait. “Bob would probably agree my father [Robert Sr., who passed away years ago] was an extremely hard taskmaster. He demanded an honest day’s work out of anybody that worked for him and I do the same. I think that’s a good work ethic. I’ve made a few enemies in my life but I’ve made many more friends and associates,” the elder Harris says. “The same ethics that were instilled in me, I’ve instilled in my son. And that’s really paid off for him. Bob is probably one of the premier stainers and decorative floor finishers in the world.”

Bob attributes much of his success to his father’s influence. He remembers some sage advice he gave him a long time ago: “If you get to the upper echelon you can take your skill and go anywhere you want. And that’s what I’ve done,” says the younger Harris, who has conducted seminars everywhere from South Africa to Spain and beyond. “His words of wisdom are now reality.”

The elder Harris also believes that staying on schedule is probably the most crucial aspect of any job. “I’ve built a lot of things in the last 35-40 years. And I’ve built them all on time and on schedule,” he says. To be successful time and time again, “Put your work schedule on a graph and follow it to a T.” As for judging the quality of workmanship, Harris believes it’s a learning process not an inherent trait. It will come in time.

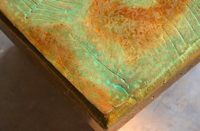

As a whole, concrete masonry has been a rewarding career, says Harris. He says he’s living comfortably and continues to work because he wants to, not because he has to. In addition to small jobs for local cities and counties, he’s also dabbling in the decorative concrete arena, staining and stamping friends’ and neighbors’ garage floors, patios and the like — something his son taught him to do.

“I love the out of doors and I like making things and I don’t mind getting dirty when I do,” Harris says, noting: “When the concrete trucks pull up, it’s like the start of the football game. I get like an adrenaline rush.”

As far as young people starting out, he says cement masonry is a pretty good career choice. “Many young people have started with my company and have branched off on their own,” says Harris. “It keeps you healthy because it’s extremely hard work. And if I had it to do all over again, I’d do the same thing. Only I would have profited more if I knew then what I know now,” he adds with a laugh.

According to his son, Harris has always been willing to help people who needed a break in life. He’d offer them a chance to have a career and an opportunity to better themselves. “My father has always been and will always be a workaholic,” the younger Harris says. “He’s a very driven man who stays extremely focused. He sets goals and does whatever it takes to achieve those goals. All of us [Robert Harrises] are workaholics. I don’t know if that’s a good thing or a bad thing. We like our work. No, like is an understatement. We love what we do.”