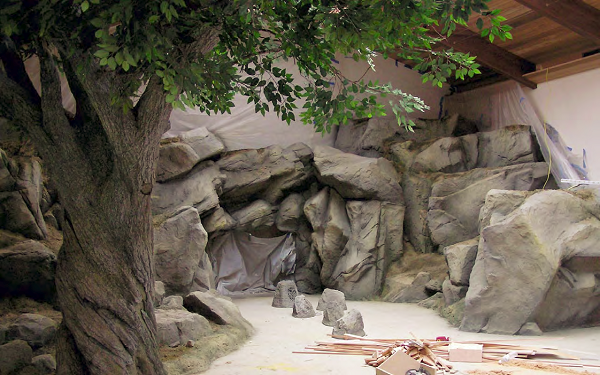

Artistry, fantasy and heavy-duty craftsmanship converge in creating natural-looking artificial environments from synthetic rock panels. Applications range from animal habitats to luxury homes, with parks, restaurants, shops and hotels in between. There seems to be no limit to the creative possibilities of this medium.

Synthetic advantages

Synthetic rock panels have several advantages over natural stone. On a large scale they are obvious. A 40-foot zoo environment or a backyard cliff would be nearly impossible to install using heavy stone, even if the materials could be found. But the weight advantage also applies on a smaller scale, say with a garden wall.

|

|

Jim Jenkins, president of Synthetic Rock Solutions and owner of training consultancy JPJ Technologies Inc. in Sheridan, Ore., has installed both. He says that stone installed on a building facade weighs in at about 21 pounds per square foot. Cultured stone installed with mortar weighs about 15 pounds per square foot. But the fiber reinforced cement composite panels he manufactures in thicknesses from 1/4 inch to 1/2 inch weigh a mere 7 pounds per square foot. And they create a monolithic structure, as opposed to segments created by natural or cultured stone.

They may be thin, but these panels have strong relief. And they may be light, but they are strong. Jenkins says his panels deliver 12,000 psi of compressive strength.

Another significant advantage over natural stone comes during installation. An experienced mason with a tender may be able to lay 40 to 50 square feet of stacked stone wall in a day. In contrast, a comparatively inexperienced workman can install 600 square feet to 800 square feet of synthetic rock panels in a day.

Finally, these panels offer designers and customers artistic control. David Long, president of Lakeland Co. Inc. in Rathdrum, Idaho, was able to build a residential client a custom “mountain” 26 feet high and 75 feet long with multiple waterfalls dropping into a man-made creek bed leading to more waterfalls downstream. Another project was a “man-room” where a hunter’s trophies will be displayed on synthetic stone cliffs under a man-made tree.

“(I’m a) geo-illusionist trying to make the client’s environment a Garden of Eden,” Jenkins says.

|

|

Fabricating with the right materials

Both Long and Jenkins advocate sharing best practices with the industry, even with potential competitors. “The better quality that people in our industry deliver, the more work we’ll all get,” Long explains. For example, Jenkins began training contractors in 1996 and has trained more than 10,500 people since then.

Synthetic rock panels start with a mold taken from actual rock. The panels may be fabricated in the shop or on-site, using the mold to shape glass-fiber reinforced concrete (GFRC). A key factor in the durability and longevity of the finished project is the quality of the GFRC. Long emphasizes the necessity of adhering to ASTM standards, including the requirement to use the proper amount of hardening agent, 4 percent to 5 percent alkali-resistant glass, and Type I portland cement. He describes seeing projects where contractors tried cutting corners on materials, only to end up with panels that chipped and crumbled within a couple of years.Ray Robinson of Robinson Earthscaping, Deadwood, Ore., describes installing the panels: “The GFRC panels are wired in place and then concreted to the rebar. Than a 70-grit fine sand, lime and cement mixture is placed between the panel faces. This is padded with latex rubber pads to match the rock texture. Then about four hours later the major cracks are carved to match rock panel cracks.”

Color makes the difference

While the mass of the rock, and the bulk of the work, lies in the structure, it is often the color that makes or breaks the project. Long calls it the 90-10 rule. “If the last 10 percent — the color and finish — are not right, the whole job is ruined. On the other hand, you can sometimes save bad rock work with creative color.” Jenkins says. “In replicating rock, coloring is the most obvious key to success or failure. It either rings true or it’s a near miss.”

Both agree that the secret to natural-looking synthetic stone is creating randomness and variation using multiple colors. Jenkins claims that the average rock, even one we might view as gray or red, contains at least 14 different colors. For a trade show booth, he created rock using 28 different colors.

Both agree that the secret to natural-looking synthetic stone is creating randomness and variation using multiple colors. Jenkins claims that the average rock, even one we might view as gray or red, contains at least 14 different colors. For a trade show booth, he created rock using 28 different colors.

Coloring synthetic rock is an artistic endeavor, with the panels in the place of the painter’s canvas and a variety of tools for applying all kinds of media. In fact, craftspeople often modify existing coloring materials or create their own to get the effects they are after. Research, experience and a lot of trial and error — “about 3 million trials and errors,” according to Long — are behind the most successful stone panel contractors.

Typical concrete coloring agents can be used to color GFRC stone panels, including color hardeners, acrylics and reactive acid stains. A base coat or overlay applied to unfinished rock panels blends the differences in color between the GFRC and the grout. Long likes using multiple products to create different effects that mimic the variations in real rock.

Typical concrete coloring agents can be used to color GFRC stone panels, including color hardeners, acrylics and reactive acid stains. A base coat or overlay applied to unfinished rock panels blends the differences in color between the GFRC and the grout. Long likes using multiple products to create different effects that mimic the variations in real rock.

Jenkins traces the history of coloring stone back to the natural sources used for dyes and paints — plants, soil and minerals were all emulsified to create coloring agents. He has colored synthetic stone to match gravel already on a site by screening fines and emulsifying them to make a stain that blended perfectly.

More typically, contractors experiment with paints and washes. Paints that stay on the surface of a panel will eventually peel, but diluting paints makes them thin enough to penetrate the porous GFRC. “In the old days we diluted household paint,” Jenkins says. “Now with more research we’ve moved to using pigment in a triple-blend polymer that matches the composition of the panel for better bonding and color-fastness.”

Whatever the medium, a contractor can replicate the look of natural stone using a variety of application techniques.

First, Jenkins says, all rocks have speckles. Speckles can be created by applying color with aerosol cans that “spit,” using piston pumps or airless sprayers and blowing the color with a fan, or even flinging color from a paint stick with the flick of the wrist. Speckles can also be created by adding mica quartz to a light wash that is applied after the top-coat begins to set.

First, Jenkins says, all rocks have speckles. Speckles can be created by applying color with aerosol cans that “spit,” using piston pumps or airless sprayers and blowing the color with a fan, or even flinging color from a paint stick with the flick of the wrist. Speckles can also be created by adding mica quartz to a light wash that is applied after the top-coat begins to set.

Other techniques include skimming — using a rag, a piece of plastic or a brush to skim over the high points of the rock texture — or daubing with an old brush to add or remove color from certain areas. Color hardeners can be spot-applied with a trowel or even an old glove to add highlights.

Washing acrylic or latex diluted in a high volume of water over a vertical surface adds natural-looking color. Water migrates down the vertical face channels and concentrates in the valleys, adding more color and creating a deepening effect.

There are some more unusual techniques too. Glazing, a technique borrowed from faux painting, creates translucent colors and different sheens. Tinted sealers also alter the color and sheen. Using specialty aggregates in the GFRC and washing the surface about an hour after curing begins results in a rough sandstone look. Painting veins using an airbrush or paintbrush adds dark color to cracks and crevices that subsequently look like shadows when a lighter color is washed over them.

Whatever technique is used, it is as much an art as a science. Long says it boils down to “a certain amount of natural artistic ability — what looks right to the eye. When you try to overwork it, it looks contrived. Over time we’ve developed proven methods that can be duplicated and used to train our personnel.” Jenkins emphasizes that even though coloring rock panels has an artistic angle, following tried and proven procedures can make even a beginner into an artist. And, like any other art form, there are techniques for modifying the look, even correcting mistakes; for example, washing more colors over white speckles that stand out too boldly.

It is difficult to describe an unusual synthetic rock panel creation because each one is unique and vastly different from any other, but the arctic environment created by Lakeland Co. for the museum at Rolling Hills Wildlife Adventure in Salina, Kan., ably demonstrates the versatility and creativity of this industry. After the gray stone was fabricated and colored, icicles were cast from clear resin and mounted with studs. These were overlaid with “snow” created with white portland cement, which was lightly airbrushed with just enough teal and purple color to create a cold-looking tint. The result is almost impossible to distinguish from the real thing.

It is difficult to describe an unusual synthetic rock panel creation because each one is unique and vastly different from any other, but the arctic environment created by Lakeland Co. for the museum at Rolling Hills Wildlife Adventure in Salina, Kan., ably demonstrates the versatility and creativity of this industry. After the gray stone was fabricated and colored, icicles were cast from clear resin and mounted with studs. These were overlaid with “snow” created with white portland cement, which was lightly airbrushed with just enough teal and purple color to create a cold-looking tint. The result is almost impossible to distinguish from the real thing.

Robinson defines the role of the visionary artist in the whole process. “It’s been my experience that when a customer calls me it’s because he wants an expert to tell him what he wants,” he says.

Long concurs. “We’re in the excitement business. We help customers envision and create their dream environment.”