Decorative concrete contractors have taken concrete all kinds of places: indoors and outdoors, underfoot and up the wall. But for a subset of concrete artisans, the decorative canvas is the whole house.

While most “concrete homes” end up looking like the usual frame house – rectangular – there are designers who use the strength and versatility of concrete to create homes that are shaped, sculpted works of art.

“These are structures that don’t rely on the bulk of concrete, but on shapes that provide structural strength and integrity,” according to Jim Kaslik of Cloud Hidden Designs LLC, based in Gilbert, Ariz.

Often, thin-shell concrete homes are built using dome shapes, but not always, he says. “The shapes don’t have to be round – they can be zig-zag, groins, arches of all kinds.” He explains that the concrete in these shapes is in compression, and “concrete is great in compression. It won’t crush itself.” Rebar or mesh is used to impart tensile strength, holding the concrete together.

Released from the confines of the straight line, there are as many approaches to thin-shell construction as there are artisans practicing it. This article will concentrate on two types, using balloon air-form domes and free-form organic forms.

Air forms

Dome-shaped inflated air forms first came into the public eye during the post-World War II building boom when they were used to fill an acute need for storage buildings. Lloyd Turner, an artist, inventor and retired architect, saw the potential to turn these temporary spaces into permanent structures. His idea was to spray the inside of an inflated form with urethane foam insulation and solidify the structure with reinforced shotcrete.

In the 1960s Turner used this technique to build his own concrete home outside Santa Cruz, Calif. He started with architectural forms of paper-thin fabric that he inflated at low pressure with a small centrifugal fan. The interior was sprayed with urethane foam insulation, followed by shotcrete reinforced with steel fibers. The inside was painted – no plastering was needed, as the shotcrete coat was smooth. On the outside, Turner brushed on stucco for protection against falling tree branches and foot traffic and finished it with acrylic latex paint. Turner has lived in the house for more than 40 years and has yet to see a crack, despite numerous earthquakes.

Jim Kaslik of Cloud Hidden Designs is a residential designer who is using inflated domes in installations all around the country. He collaborates on his designs with a structural engineer and always works within the parameters of the International Building Code so that he doesn’t have to apply for variances. He also uses traditional residential and concrete contractors to construct the homes. “These designs don’t require some kind of specially trained dome contractor,” he says. “They need a good builder to get a quality result.”

Kaslik uses mathematical formulas to create the shapes he favors, usually intersecting domes. “The shape has to be one that will inflate right,” he explains. “It has to be circular in at least one direction in order for the shape to be taut in all directions.”

On-site, the vinyl polyester form is inflated and foam insulation sprayed on the inside. Then the contractor ties a cage of vertical and horizontal rebar to the foam and sprays the concrete against it using a pump with an air compressor.

A variety of standard concrete mixes can be used. Kaslik has contractors use a typical spray mix from their local ready-mix supplier. Kaslik seldom uses additives but suggests a relatively high percentage of portland for compressive strengths of up to 4,000 psi. A drier mix is usually preferred for spraying overhead, he notes.

Free form

While air form thin-shell concrete construction is versatile and varied, it is limited to shapes that can be inflated. There seem to be no limits on the designs created by Steve Kornher from his Flying Concrete studio near San Miguel, Mexico. Inspired by the famous Spanish architect Antoni Gaudi, Kornher draws on his background as a masonry contractor and a potter to create fluid shapes that curve and swoop.

He uses pumice, cement and lime to mix a concrete that is light and strong enough to be used for a roof, supported by columns every 10 feet or so.

To create his roofs, he starts with a shape made of driveway mesh. For tighter curves he uses galvanized mesh. He trowels on the first layer of the pumice mix about 3/4 inch thick and allows this to set for two or three days. Then he builds up the roof in layers to the shape and thickness he wants, usually about 6 inches. He incorporates layers of welded wire mesh inside the pour to prevent cracking. Lately he has been working with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fibers from Japan for added crack protection in the final exterior polish coat.

Jeff Beard, a sculptor and online bookseller, needed more storage and studio space. “I had thought of repurposing shipping containers, which are all the rage,” he says. “But I couldn’t bring myself to do a box, even just for storage.” He came across Kornher’s work in a book called “Home Work: Handbuilt Shelter” by Lloyd Kahn, and he was so intrigued, he traveled to Mexico for a Flying Concrete workshop. Now a Kornher creation is underway near Beard’s home in Crestone, Colo.

This building is a good example of the organic, adaptable nature of Kornher’s construction.

“The overhangs outside are showing some Gaudi-like distortions,” says Beard, a Gaudi fan. “There will be eight buttresses at least, each one different. There are round windows and oval windows. There are not really any right angles.” The building is designed for future changes and adaptations, a good thing because Kornher predicts it will last 400 years.

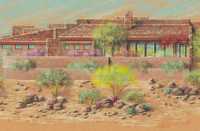

Kornher’s largest work in progress is a house and outbuildings belonging to his seasonal neighbor in Mexico, Tim Sullivan. New extensions and additions have been added over the past 14 years, making the ranchito seem almost like a living thing. Kornher and Sullivan have created unique arches, vaults, domes, and even doors and rails, while Sullivan has experimented with brilliant colors painted on the plastered concrete surfaces. “Steve’s work is always evolving,” Sullivan says. “He’s talented and he loves what he does. He definitely has a gift.”

Thin-shell concrete construction may not appeal to everyone, but for those who want to literally think outside the box, it is an opportunity to create long-lasting live-in art.