A visually striking public art project near the University of Simon Fraser in Vancouver, British Columbia, was the result of science and engineering intersecting, orchestrated by a concrete artisan who was skilled enough to make it happen.

Nolan Mayrhofer’s Vancouver-based concrete artistry firm, Szolyd (pronounced ‘solid’) Development, works primarily with precast concrete. In particular, he is licensed to work with Ductal, an ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) made by international concrete company LafargeHolcim.

Mayrhofer, 43, has a reputation of accepting concrete work that few, if any, other companies can or want to take on. “If an artist or designer has a concept they call us and say, ‘We have this idea but five other people turned it down because they don’t think it’s possible,’” he says.

Mayrhofer has used UHPC for 15 years, so he and his crew are generally beyond the research and development phase with their projects. This art project, however, called Ecological Social Modules — or EcoSoMo for short — was more of a challenge.

Along the beaten path

Along the beaten path

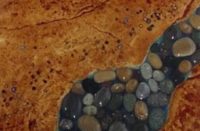

EcoSoMo, installed along a path in the community of Burnaby Mountain adjacent to SFU’s campus, is a series of six modules designed to fit together in multiple ways. It was commissioned by the SFU Community Trust and designed by Vancouver artist Matthew Soules. Szolyd fabricated the positive models, developed the molds, cast the components and installed the project.

Mayrhofer says Soules had heard about Ductal and wanted to use it. “We don’t use UHPC products for everything we do, but there are times when a material like UHPC fits in and it does for this project.”

Fifty modular pieces of concrete were combined in various ways to construct 13 sculptural clusters placed along 800 feet of a public walkway. Each concrete piece is inscribed with information about Burnaby Mountain in the modern-day alphabet, Braille and pictographic lettering created by Canadian graphic designer Ross Chandler.

Two of the clusters — which are topped by a birdbath and a plant holder dubbed a “plant volcano” — illustrate the ‘ecological’ part of the project’s name. Two others, which combine to form a seating area, exemplify EcoSoMo’s ‘social’ aspect. Still another cluster has notches, inviting the public to place small things in the recesses.

“I’m a big believer in the strength of dense urban neighborhoods and what they offer socially and ecologically,” artist Matthew Soules told “Georgia Straight,” a Canadian weekly newspaper. “This project, in its subtle way, is trying to be a generator of that.”

Challenges and strengths

The challenges involved making molds that could be used multiple times without degrading. The crew made six molds and cast up to 15 of each, allowing Soules to explore the concept of reproduction. In a video taken June 2015 during the art project’s unveiling, Soules said, “It’s a study in seriality, multiplicities and an investigation into how modular systems can produce diversity.”

More people now live in urban centers like apartments and condos, so public spaces are gaining importance. “A project like this is functional furniture where people can gather,” says Mayrhofer, adding that it’s attractive to animals and people and incorporates nature.

From start to finish, the EcoSoMo project took nearly five months. Soules gave Mayrhofer a 3-D model of each shape, and a computer numeric control machine made each face out of medium-density fiberboard. A positive of each shape was then made.

From start to finish, the EcoSoMo project took nearly five months. Soules gave Mayrhofer a 3-D model of each shape, and a computer numeric control machine made each face out of medium-density fiberboard. A positive of each shape was then made.

Glyphs (pictographs) were laser cut out of rubber, applied to the MDF and enclosed with fiberglass. The mold had to break apart in multiple ways, both on the outside and inside, and remain strong enough to fit together again and hold in place. “It was a pretty complex project … super challenging,” Mayrhofer says.

Ductal handles tensile pressure extremely well, while regular concrete handles compression pressure very well. (Tensile strength resists being pulled apart, whereas compressive strength resists being pushed together.) Regular concrete needs to be reinforced with rebar to withstand a high level of tensile pressure, but UHPC doesn’t.

Ductal, which is reinforced by stainless-steel or metallic fibers, needs no steel rebar, so it can be cast incredibly thin. The thin parts of the sculpture that look like “wings” with an inscription and the plant volcano’s cantilevered base could only have been done with UHPC.

Mayrhofer discovered that regular concrete has a compressive strength of 2,000 to 5,000 psi, flexural strength of 570 psi and direct tension strength of 450 psi. It offers weak abrasion resistance and is permeable to chloride penetration, which can discolor and degrade concrete over time.

By contrast, according to company literature, Ductal is more than six times stronger than conventional concrete, offering compressive strengths up to 30,000 psi. It has a flexural strength of up to 6,000 psi and direct tension strength of up to 1,450 psi. Its abrasion resistance is similar to natural rock and it’s almost impenetrable to chlorides with no carbonation.

Repeat after me

Repeat after me

Ductal allows Mayrhofer to texturize forms that will maintain their detail over time without degrading. Because Ductal requires no aggregate, it can be cast into fine textures almost like porcelain. And even though the shells are only about an inch thick, the inscriptions on this art will last for decades.

Mayrhofer says the issues he experienced were minor considering the project’s scope and challenges. The biggest challenge was maintaining the texture on up to 15 castings. “The texture started to degrade to the point where we were losing some fine detail when we were getting into the multiple castings,” he recalls. “The rubber molds were wearing out,” and toward the end they had to improvise some of the texture.

With his skill, experience and determination, Mayrhofer has become the go-to guy for challenging projects, but it’s taken a toll. “At the end of the day, we proved this material has the structural and aesthetic qualities for this type of application,” he says. “I have a lot of pride in the work but it hasn’t been very profitable.”

Although he’s not classically trained in art or engineering, Mayrhofer has been drawn to those aspects in his concrete work and has learned through trial and error. Early experience with making mosaics with his company Stone Design led him to offer concrete flooring instead of mosaics which, in turn, led to precast. In 2003, Mayrhofer founded Szolyd to offer precast landscape pieces and countertops.

He doesn’t like to take on projects that are just one-offs, he says. “I want to do things that can be repeated. Once you invest time and money into a mold, you want to use that mold until it disintegrates. That’s my focus now and I’d say this job was a stepping stone because it had all the elements of good design and repeatability.”

The tricky projects, though rewarding, are “next to impossible” where making money is concerned. He says he’s now a little more “risk averse” given the chances he’s taken over the years with little in return. “We get some fascinating calls and a lot of them are possible, but sometimes you have to do the calculations and decide if it’s worth it.”

Mayrhofer is not the type of guy to sit around and wait for the phone to ring. He started another company, Landscape Furnishings, to focus on precast outdoor items for public and private spaces. At press time, Mayrhofer said he was deep into planning a unique concrete product.

“I can’t say anything about it yet, but it’s a home furniture item that’s going to blow up,” he says. “The world’s never seen a product like this.” Stay tuned.

www.szolyd.com

www.landscapefurnishings.com

www.sdconcrete.com

www.mendrestoration.com

Watch a video unveiling the project on YouTube

Project at a Glance

Project: A public art project in Vancouver, British Columbia, consisting of 50 precast molded shapes using Ductal UHPC combined in various ways to create modules along 800 feet of a public walkway.

Scope of work: An artist, Matthew Soules, msaprojects.com, designed the work. Szolyd Development, szolyd.com, led by Nolan Mayrhofer, fabricated the positive models, developed the mold technology, cast the components and installed the project. Canadian graphic artist Ross Chandler designed the glyphs and writing. rosschandler.ca

Most challening aspects: The six molds were used repeatedly to get a variety of shapes. The texture had to be fine enough to allow for writing and glyphs on the surface and be strong enough to be molded multiple times.

Products used: Ductal ultra-high performance concrete by LafargeHolcim; lafargeholcim.com