All it takes is a single phone call to know that Gore Design Co. is not your average concrete artisan – whether they pick up or not. “Hello and thank you for calling Gore Design Co.,” says the studio’s answering machine in a tinny, modulated tone. “My name is Billy Bob, the friendly robot who answers the phone while the humans are busy creating with concrete.” The voice of Billy Bob may, in fact, be the electronically altered voice of Brandon Gore, founder of the design firm, but that doesn’t make his message any less true – the humans have indeed been busy with concrete.

Gore is a 32-year-old survivor of the corporate grind. Ten years ago, as a sales manager for the Marriott hotel chain, he was making great money, traveling incessantly and, he says, “slowly dying inside.”

Gore is a 32-year-old survivor of the corporate grind. Ten years ago, as a sales manager for the Marriott hotel chain, he was making great money, traveling incessantly and, he says, “slowly dying inside.”

He took a leave of absence from Marriott – “I wanted to do something more honest with my life,” he says – with no set plan for what that more honest something would be. But he didn’t let that stress him out. At the time, the housing market in Tempe, Ariz., (where Gore lives and works) was booming. Many of Gore’s friends were making good money flipping houses, and that was a path that he, too, considered. “Architecture has always been a part of my life,” says Gore, whose father and grandfather were both civil engineers. “I wanted to do something that would allow me to be more creative, something that would let me use my hands.”

And flipping houses may well have been the path he chose, were it not for a fateful ride on his mountain bike through the Phoenix suburbs. Riding through an area of look-alike housing developments (or, as Gore calls it, Whoville), he stopped to admire an expertly designed home at the base of South Mountain. Something about the house struck him, he says, but he didn’t think much more about it until a few days later, when he stumbled across a magazine article about the house. It turns out his chance encounter had been with the critically acclaimed home of architect Eddie Jones, and one of the things the article highlighted was the cutting-edge concrete countertop Jones had chosen for his kitchen. For Gore, the picture of that countertop was a glimpse into his future.

Gore’s first step from random magazine article reader towards successful and edgy concrete studio owner was taking the very first countertop class offered at Buddy Rhodes’ studio in San Francisco. “When I look back at it now,” Gore says, “it was very simplistic. Build a box, mix concrete, dump it in – you’re done.” But however humble, that first class had hooked Gore completely.

Not long after that, around a year after he took his leave of absence, Gore rented a studio, despite the fact that he didn’t have a single project lined up. For a year, he spent most of his time rearranging his shop, making concrete pieces and photographing them to build up a portfolio. And then finally, he got a call. A 5-foot-by-1-foot counter for a project in Flagstaff. He was ecstatic – and the work kept coming.

“I was very lucky with timing,” Gore says. The housing boom in Arizona was good for concrete fabricators, too, as it turned out. “Any fool could walk into that situation and grow a company,” he says.

About a year after that first job in Flagstaff, Gore got a call from a local metal sculptor who was looking for a really unique sink. Gore says that at that point, he felt like he was sort of pigeonholed, doing predominantly West Coast-style countertops, and this client gave him a chance to really reach, designwise. Gore went through 15, maybe 20 working prototypes on the wet-cast sink before finally settling on something that both he and the client were thrilled with. The Erosion Sink, as it’s since been dubbed, cost Gore about three times (in materials alone) what he charged for it – but this was the sink that really saw Gore Design take off.

Evolution through Erosion

When Gore first started the company, he wasn’t at all sure he would succeed. “It was more or less an experiment to see how far I could get with this,” he says. “I sort of expected to fail at a certain point.” After a few years, it became clear that failure was not imminent, so Gore decided that his benchmark for succeeding was to be published in Dwell magazine.

The Erosion Sink would get him there. It was covered in a local design magazine first, which caught the attention of a home design blog, which wound up on a Dwell editor’s screen. After three months of going back and forth with the editors for photos and follow-ups, Gore walked into a Barnes & Noble one afternoon, picked up the latest Dwell, and there was his sink. “Literally, that was the day everything change for me,” he says. “My website went from around 20 hits a month to 7,000 to 8,000!”

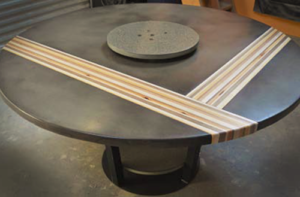

The Erosion Sink marked the beginning of the firm’s commitment to wild, creative custom fabrication. Gore works with a small staff of concrete artisans, and they do custom GFRC fabrication for clients all over the world. The Erosion Sink has become one of their most popular designs (like the rest of their work, it’s now done with GFRC), and clients frequently request its organic, rippled look for their own custom sinks. For other custom work, the Gore crew draws their inspiration from nature, anatomy and their own wacky imaginations.

But not all of the work that Gore does is from-scratch custom commissions. The firm also has eight standard sink molds that they use regularly.

The contrast between standard sinks and custom work is an important one. Gore Design’s rate for a standard piece is much lower than that for a custom one, but Gore says the profit margin on a standard job is often much higher. He might spend 40 to 50 hours perfecting a custom design, whereas a standard sink of the same size take 3 to 4 hours total.

Still, the custom work is what gets the attention of the press and of future clients, and it’s also how you “keep the joy in your work,” Gore says. “The perfect job for me is when a client commissions one custom sink and three standard sinks. We get to have our cake and eat it too.”

Another important aspect of Gore Design’s business model is its marketing strategy, which takes advantage of the studio’s trademark edginess. Billy Bob is one facet of this strategy, and another is the company’s website. Gore went through three Web designers in the process of revamping the site before eventually settling on building it himself. It’s primarily a portfolio site – “at the end of the day, all you have is your photos,” says Gore, a firm believer in the importance of hiring professional photographers. But the site also tells the story of Gore as an artist moving past traditional concrete into the creative landscape of GFRC fabrication.

Gore says the company used to have a more straightforward image, adopting strategies, like many small firms, that made them appear bigger than they were. “I got over that,” he says. The company has had a staff of three for three years now. Gore is very comfortable there and, in fact, extols the virtues of a small organization. “Do not grow,” he says. “Stay small – you can move, adapt, change. Big companies can’t weather the storm.”

But while Gore doesn’t intend to grow, that doesn’t mean he plans to stay the same. In the coming months, Gore has plans to change the company’s approach yet again. Currently, the firm enjoys steady work despite the recession, but much of it is starting to feel a little too familiar. Gore and his team are after a creative challenge. To that end, the company plans to limit the number of jobs they take on, focusing only on projects that really inspire them. “If it’s going to be a challenge, if we’re going to be racking our brains to figure out how we’re going to do it – that’s what we want,” says Gore.