The process for “free-forming” a fabric mold — for all kinds of creative, ripply results — is a little different but will include many of the same steps as basic fabric forming. The biggest difference is that you will be working on the outside of the mold first.

We used fabric-forming to create a free-floating shelf.

1. The armature

This was the easy part. As we were making a shelf, our armature only needed to be a flat platform raised high enough for us to drape the fabric over and achieve our desired height. We simply used a piece of melamine cut to the size desired for the shelf — 12 inches deep by 36 inches across — with 24-inch legs.

We then sealed the raw edges of the melamine with tape. Given that we will be adding a Bondo-resin mix to this surface and sanding, there was no need to worry about the lines from the tape transferring to the mold.

After applying the tape, we applied two coats of mold release wax, buffing both coats. This will ensure that we can remove the armature once the fabric has stiffened.

Note: You can ease or round your edges of the armature board if you do not want a crisp corner on the final top.

2. Forming the fabric

2. Forming the fabric

Now that the armature is ready, we prep to wet out the material. There are a couple of ways this can be done. You will need to have a few things ready when you do this method (beyond those in the Basic Fabric-Forming Tool List). Here is the process and the things you will need.

First, we will lay our fabric on the armature and cut it to the desired size and shape.

Allow it to drape about 3 inches longer than you intend the piece to be, in case you decide to cut the bottom of the cast piece to clean up any raw edges. This is not always necessary — the need to do it is determined by your mix and your ability to cast vertical surfaces. If you can cast vertically to a finished edge, make your piece the exact size you want. Then trowel to a finished state at the top of the mold.

Once your material is cut and ready, get all your tools ready for wetting the material, the next step. You will need a hot glue gun warmed up and ready to glue. You will also need extra armature pieces to help hold some of the drapery in place. You can use PVC pipe of different diameters or wood dowels — or anything, really — to hold your fabric in place. I prefer the PVC as it releases from the mold much more easily.

3. Wetting out the fabric

Once all your pieces are ready, you will then wet out the fabric. There are two ways to do this. One is to use resin and the other is to use an acrylic polymer. If you use resin, you will only have a small amount of working time with the material before it stiffens up, so this is best reserved for smaller molds. Make sure you are ready with your design and your extra armatures, or you may be wasting material and starting over.

Wetting out the fabric using resin

To create our mold we mixed a quart of resin with 1 percent of a quart (about 10 cc) of MEKP hardener. This is critical to have enough working time with the material. Once the resin is mixed, we saturated the material in the resin, then draped it on the armature.

Once it was in place, we began to tug on the fabric in different areas to get our drape to the style we wanted. The weight of the resin (or polymer) is the trick here. The weight will pull the fabric down, giving you the draped effect.

You will now need to use the glue gun to tack your fabric in place to hold the shape. You can do this with the hot glue and your extra armatures. For our mold, we used the hot glue and tacked the fabric onto the armature that was already there.

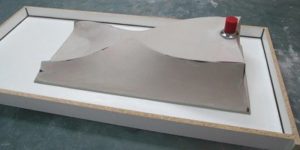

For the flares on the fabric, the areas away from the armature, we glued PVC pipe to the base of the armature to hold the fabric in the place we wanted it.

Note: This is where the different sizes of PVC will come in handy. If you want a bigger curve, you will use a wider pipe. Also, remember to wax the pipe so that it releases from the mold.

Once the armatures were in place and the fabric in the basic shape we wanted, we did the final details.

There are areas in your mold that will have wrinkles that you will not be able to cast into, either because they are too tight or too undercut. There are a couple ways to deal with this.

On the top of the mold, the part that will be the shelf, we cut the fabric and overlapped it on top of itself. We used a little extra resin here to make sure they bonded. We also used a little fiberglass matting here to ensure that the mold holds together.

For other areas that we could not manipulate without changing the design, we used Bondo in the mold to shape these wrinkles out. We also used Bondo where we cut the fabric and laid it over itself. Just a little bit of body work, so to speak.

Once the fabric had firmed up and we had locked in the shape, we applied two more coats of resin to make the fabric rigid. This was applied to the outside of the mold and the fiberglass matting in the cut areas.

Note: We also used the fiberglass matting in areas where the mold needed a little more firming up, such as the corners and the area we had cut on the top. Be careful about using matting in areas that may have undercuts. If the matting is pinched between two folds, you may have to break the mold to get it out of the cast piece.

We applied one coat of the Bondo-resin mix on the exposed area of the inside of the mold. This gave us a little more rigidity to ensure that the mold was solid enough to remove from the armature.

We applied one coat of the Bondo-resin mix on the exposed area of the inside of the mold. This gave us a little more rigidity to ensure that the mold was solid enough to remove from the armature.

We also put a layer of matting on the flat part of the shelf along with a couple of 1-by-2 wood strips to hold the mold flat.

Once we removed the armature, we went through the Bondo-resin finishing steps that were laid out in the November/December issue (and can also be found online at ConcreteDecor.net), applying about four coats total and sanding to a 320-grit finish. After wax, we were ready to pour the concrete.

Wetting out the fabric using acrylic polymer

Using acrylic polymer is easier but it takes a little more time, as the polymer takes longer to dry and stiffen up. Following the same process as you use with the resin, you will wet out and drape the fabric on the armature. It will take about one to three hours for the polymer to dry to a stiff form. Once it is stiff, you will need to apply several coats of resin to the fabric to get it to a more rigid state.

With this method, using the polymer, you will have time to work with the fabric and get it to the shape you want. However, be aware that the polymer will only stiffen the fabric to a firm state. Adding resin to the fabric will be necessary to make it rigid, and this can be a trick.

With this method, using the polymer, you will have time to work with the fabric and get it to the shape you want. However, be aware that the polymer will only stiffen the fabric to a firm state. Adding resin to the fabric will be necessary to make it rigid, and this can be a trick.

The fabric can wrinkle on you if you brush too hard while applying the resin, so be gentle. After the first coat of resin, your material should be firm enough to work with. Once it is firm (after two or three coats of resin) you can follow the usual resin-wetting procedures to finish.

Note: You can use just about any polymer to make the fabric stiff, but do a test on a small amount of fabric to make sure that the one you use will give you the firmness you want and will bond with the resin. A high-solids polymer is the way to go. There are also specialized products designed to stiffen material, and you can find these at your local craft store.

Another Way to Form with Fabric

I recently had the pleasure of spending a couple of days with Alla Linetsky, of Concrete Elegance in Toronto, Ontario.

She has a process she calls “flex fabric forming” in which she casts her concrete onto felt-backed tablecloth material, then allows it to harden just enough that she can flex it without breaking it. She then bends the tablecloth material to the desired shape.

This gave me an idea. I took some tablecloth material that Alla gave me, shaped it, and applied resin to the felt side, brushing on just a couple of coats. I think I ran the resin too hot as it wrinkled the material a bit — not sure if this was from melting, shrinking or both. But it did get stiff and I was able to cast against it. It came out great! No Bondo-resin, no sanding. Quick and done.

I have not fully tested this method for larger projects, and the material, being already semistiff, was limiting to work with, but I can see great potential for numerous types of projects. Just thought I would share that. (Thanks, Alla.)

Basic Fabric-Forming Tool List

1-inch, 2-inch and 3-inch chip brushes.

1-quart and 2-quart plastic mixing buckets. You can get these at the box store, but you can find them cheaper at the auto-body supply shop.

Rags or heavy-duty paper towels.

Mixing sticks. Plastic is best as it will not absorb your hardeners.

Organic respirator. A regular respirator will not protect your lungs from the smell of the resin. It needs to be an organic one.

Palm sander or dual-action sander. There are two different types of backing for sandpaper: sticky-back and Velcro. Make sure that you get the right type of backing for your sander.

Upholstery stapler. A simple pneumatic stapler that shoots T-50 staples is easy to get. A pneumatic stapler is better than a hand stapler, which will leave you with sore hands at the end of the day. Also, a broadhead stapler is better, as narrower ones tend to cut through the material and can allow tears when you’re stretching.

Boxes of vinyl gloves. Do not use latex, as they do not hold up well with the resin. The cheap vinyl ones are the best, as you will throw them away after each mix.

Cup gun. This is not necessary for smaller projects, but it can be helpful for bigger molds. I would suggest getting used to the process before you run out and spend $150 on this tool, unless you are planning on doing larger projects right away.

A couple of pairs of all-metal scissors. You will want one for dry cutting and one for cutting material that has resin on it. You can clean these with the acetone — just be sure to do it before the resin dries. Plastic-handle scissors may melt or soften from the acetone.

Fiberglass rollers. These are also not necessary, but they are handy to have around for some projects.

Metal and plastic Bondo knives. Get these at the auto-body supply shop or a tool store like Harbor Freight Tools. You’ll pay way less than you would at the box stores.