Concrete does exactly what you ask it to. Problems with casting concrete do not arise from the concrete acting up. Problems arise when we don’t understand what we are asking for. With concrete, watch out what you ask for because you may just get it.

You can cast concrete on anything. You can cast it on wood, metal, rubber, plastic or dirt. You can cast it on whatever you want, and you will find that invariably you get what you asked for. What are we asking for? What is it that we really want? Herein lies the issue — learning what questions to ask and how to ask them.

Choosing the appropriate casting surface involves two primary variables: the nature of the material and the nature of the mold. With experience, this becomes an intuitive process, but initially this can be challenging and costly.

Understanding the casting material you are working with is a relatively simple matter that comes from experience, trial and error, and learning from the experiences of others. Every material has two primary aspects that affect the concrete’s final appearance: the textural and visible quality of the material, and the structural/chemical and invisible quality.

To grasp the nature of the mold you will use, consider several other variables. What is the finished product going to look like?

What is the concrete mix design and placement method that will be used? How will the mold be constructed? What is the cost? Which landfill are you sending the mold material to when you are done with it?

Answering these questions and understanding the aspects of the material in order to choose the right casting surface begins a circular thought process that is often inherent in design and fabrication. The thought process of design is not a linear, two-dimensional event where we answer certain questions in a certain order and . . . viola. The design process happens when all the variables are viewed in three dimensions and we methodically see what fits and what doesn’t. There is not necessarily always going to be a single right answer to a design problem, but there are often wrong answers. Our job during the design of a piece is to weed out as many wrong answers as possible.

Questions to ask when choosing your casting surface

What is the finished product going to look like? How much are you grinding? A cement finish has requirements that a piece with a heavy grind doesn’t. An easy example of the relationship between casting surface and finished product would be steel casting tables. You may be able to get a cement finish off a steel casting table, but that will require a lot of unnecessary work, and once the tables are used a few times you are taking an imprudent gamble trying to get a perfect finish. On the other hand, a steel table can prove to be a durable and inexpensive long-term casting surface for pieces that will be ground out of the mold.

The less grinding and polishing you plan, the nicer your mold needs to be. Your piece will be a reflection of your mold, so if you want a perfect surface you better have a perfect mold. The more you plan on grinding, the more crudely fashioned the mold can be. If you are going to expose heavy aggregates, don’t waste your time making the Mona Lisa of molds, because it simply doesn’t matter.

This is important in respect to cost and efficiency. If you spend a bunch of time on a mold that doesn’t matter, you are wasting money. This may seem overly simple, but I have heard a lot of people fretting over molds when they plan on grinding 1/8 inch of concrete off once it comes out of the mold.

How are you going to seal? Different sealers have different requirements in regard to the state of the substrate they are to be applied to. Does your sealer need a profile to which it can mechanically bond? If so, casting on a piece of glass or some other ultrasmooth surface may not be such a good idea. Mold releases also should be considered in regards to the sealer you intend to use, particularly if you want a cement finish.

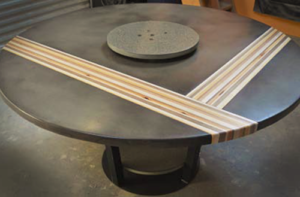

Will there be inlays? Inlays may require glues that may or may not be compatible with your casting surface. Also, certain inlays require that you cut into your mold in order for something to protrude from the finished surface, for example, as with trivets. Some sink molds also require that you plunge into the surface to eliminate the reveal in the sink mold.

How many times will this piece be cast? The long-term durability of a casting surface, the ease of mold construction, and the reality of storage all become huge factors in production situations. Many types of resins and rubbers shrink or distort over time, creating serious issues for pieces that need to maintain a certain dimension.

How long will the concrete be in the mold? The farther along the concrete is in its curing cycle, the more the concrete will reflect the casting surface. This is a function of the increased density that comes from the crystal growth in the concrete — the more concrete cures, the more dense it becomes. If you want a piece to look like the glass it is cast against, the longer it stays in the mold curing, the better the reflection. In the case of leaving something in the mold, keeping the pieces moist and covered is important in order to mitigate curling.

What mix design and placement method will be used? Are you going to vibrate, spray, hand-pack or pour? Will the concrete be floated into the mold using “The Force”?

Placement methods and the rheology of concrete dictate how the mold will need to be constructed. Mixes that are very fluid or vibrated can exert quite a bit of force on your mold, and concrete in its fluid state can find ways out of the mold. Molds that are sprayed or hand-packed require less consideration in regard to force from the concrete and fluidity considerations.

Fluid pours should go into sealed molds to avoid moisture and fine particle migration out of your mold. Sprayed and hand-packed molds don’t need to be sealed in the corners because there is not the same concern regarding migration. However, if you are after a cement finish, you will want to consider a sealed corner to avoid processing out of the mold.

For sprayed molds that are very tight (too tight to fit the hopper), you can leave one side of the mold off, spray the necessary faces, and reconstruct the mold prior to placing the fiber-reinforced mix.

How will the mold be constructed? After consideration of the issues discussed, some of the requirements for mold construction should become clear.

Something to consider — the mold needs to come apart at some point, so put down the Gorilla Glue, please. Part of the true art of mold building is building the mold that doesn’t fall apart when it is being poured, but falls apart right when it is time to demold.

What’s holding the mold together — brad nails, pocket screws, predrilled screws, double-sided tape, hot glue, construction adhesive, silicone, magnets, glued or screwed blocking? Is the fastening system and the mold surface compatible?

How much will it cost? The issue of cost is both a short- and long-term matter. I hear talk of seaming melamine because of the fear of the cost of buying something that is the right size. Really? What’s your time worth? Ask yourself, is the real cost of your material after splicing, Bondoing, painting, sanding and all the processing of the concrete (because it isn’t perfect like you thought it would be) going to be less expensive than a 12-by-5 sheet of laminate for $120?

The issue of long-term cost comprises use, waste and reusability. I remember being so happy that we could just order a pallet of melamine at a time. It was less expensive, it saved all those trips to the hardware store, and they brought it right to our doorstep. I was actually excited that my melamine bill was $700-$800 a month.

But there is a much better alternative — reusable casting decks. The cost savings and the reduction in waste is so dramatic, it makes using melamine as the primary mold surface seem crazy.

What are you wasting? I have always found the idea of using pozzolans to save the planet a bit ridiculous when throwing away dumpsters full of sheet goods every month. If there is ever a measure of the impact a concrete studio has on the planet, I would argue that the appropriation of mold material would be at the top of the list.

More considerations

The textural and visible qualities of a potential casting material are easy to determine. What you see is what you get, mostly. There are a number of variables that affect the finish of concrete, but for the most part concrete will pick up every bit of texture that a material has in it. Whether it’s the texture in Corian or the wood grain in a sheet of plywood that is underneath a heavy coating, if it is there it is going to be in your concrete. This is when the questions of surface rigidity and draft need to be considered.

Can your concrete physically release from the shape of the mold texture? Are you after an ultrasmooth and reflective surface out of the mold? Just get a piece of shiny laminate, clean it well before you pour, and you will have a smooth finish out of the mold. Regular laminate has varying degrees of texture, similar to melamine.

The chemical/structural and invisible aspects of a casting surface are a little harder to sort out. This is different from material to material. This pertains to everything from the porosity of different woods, to the chemical nature of aluminum and the effect it has on newly placed concrete, to the different types of coatings that go onto melamine and how they vary.

This aspect of casting materials can affect the finished piece in many ways, and often keeps something from looking like the surface you cast against because of poor release, water loss, or chemical reactions. It takes learning from your own experience, as well as the experience of others, to really begin to develop a grasp for this aspect of materials.

Material availability

Knowing what materials are options is one thing. Knowing where to acquire said materials is a whole other ballgame. The art of finding resources and allies is one of the primary tasks of someone in this profession. It takes scouring the earth, starting in your own neighborhood and reaching into the greater universe, all to find what helps you make your vision a reality.

A few places to search out casting materials locally: every hardware store (even mom-and-pop shops have surprising finds), suppliers to the laminate and solid-surface trades, plastic suppliers, sign shops, machine shops, art supply stores and marine/boat suppliers. If you can’t find it locally, the world is at your fingertips. A basic Internet search should provide all the resources necessary.

There are a million different mold release options, from high-tech stuff to your mama’s hand lotion.

Specialty items that achieve different looks can be found everywhere: fluorescent lighting covers, glues applied to molds, stencils, and knickknacks from the dollar store. The next time you are suffering through a trip to buy a Barbie doll for your daughter (or son), think, “How cool would that be cast in concrete?”

Happy casting!