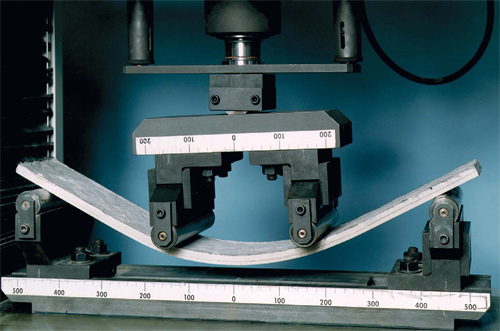

High-performance fibers made of PVA, which is short for polyvinyl alcohol, were developed some 20 years ago by Kuraray, a Japanese company. When added to concrete or mortar, the fibers develop a molecular and chemical bond with the cement during hydration and curing. The result: concrete with high tensile strength and amazing ductility whose makeup can significantly reduce a project’s steel load.

“Polyvinyl-alcohol engineered cementitious composite, PVA-ECC, was developed to be used in high-rises for earthquake remediation because it eliminates vertical sheer,” says Jim Glessner, owner of GST International LLC, a Nevada-based company that manufactures as well as distributes an array of specialty concrete products.

“While concrete is very strong side to side, any vertical movement will make it break or crack,” he continues. “PVA-ECC allows movement like a blanket. This stuff won’t crack, but it does microfracture to allow it to bend. It’s literally bendable concrete.”

This sets PVA-ECC apart from glass-fiber reinforced concrete (GFRC) which is subject to vertical shear. According to materials on the Kuraray Web site, PVA-ECC has strain-hardening capacity, while GFRC has none, meaning a PVA piece is less prone to failure when it cracks. “Your mechanical numbers on tensile and flexural strengths are far superior with the PVA fiber versus glass or steel,” Glessner notes. When it comes to architectural and decorative applications, Glessner says the engineered cementitious product can be used for anything large or small, from vertical walls and horizontal countertops to precast slabs and patch-and-repair shotcrete.

To use or not to use

There is one big drawback to using PVA fibers, Glessner states – “otherwise everyone would be using it.”

Mixes with PVA fibers are really difficult to formulate and use, he says. “Coming up with the right mixture takes time. Sometimes it even takes years.”

The PVA fibers tend to clump and bind to each other in the mixing process, Glessner says, “something we call the hairball effect.” To help alleviate this problem, his company, along with some others, makes a special dispersant to make the contractor’s job easier.

Not everyone agrees with Glessner that PVA is hard to use. Jim Ralston, president and owner of Urban Concrete Design in Phoenix, says he’s been using the product for years to make a lot of different things. What those things are in particular, he’s not revealing. “But I’ll tell you I’m using it to create 5-by-10 foot slabs I sell to fabricators who use them for countertops. They install them like granite,” he says. He mixes PVA with three other fibers, including GFRC. His only complaint is that PVA is not cheap.

“Hands down, it’s the best fiber there is on the market. I’m fully on board with that stuff,” Ralston says.

On the other hand, Brandon Gore, owner of Gore Design Co. in Tempe, Ariz., has no interest in incorporating PVA fibers into any of his eye-catching sinks. “I’m satisfied with the results I get from using GFRC and I don’t see any reason to switch,” he says. One of his main suppliers has convinced him GFRC is more affordable, easier to work with and structurally more adept.

And then there’s Jon Schuler, owner of CreativeCrete in Murphys, Calif., whose projects involve sinks, countertops and cast-in-place creations. “Everything we make has PVA fibers,” he says, adding that he only uses hand-placed GFRC when a certain look calls for it.

He’s been using PVA for the last four or five years. “And we’ve never had an issue with dispersing fibers. It’s my number one recommendation, followed by a PVA-glass combination,” Schuler says.

“PVA is an incredibly stealth fiber,” he continues. “When I grind and polish, I don’t worry about fiber showing up or sticking out.” He currently loads 1/2 pound per cubic foot, which he says gives him the same strength as 5 pounds of glass fiber.

“That (amount of PVA) is two to three times what the other guys are loading,” he notes. “We produce many products that require PVA fiber loading as high as a pound per cubic foot. Once you get past a pound, that amount of fiber acts more like an aggregate.”

The PVA fibers allow him to cast pieces much thinner than traditional concrete. “The thinnest I go is about an inch. That’s my comfort zone to maintain the looks we are known for.”

As for the cost, Schuler says, “It’s not some superexpensive product. I think you’re shooting yourself in the foot if you don’t use it. It really increases impact resistance and surface hardness.”

As for the cost, Schuler says, “It’s not some superexpensive product. I think you’re shooting yourself in the foot if you don’t use it. It really increases impact resistance and surface hardness.”

Bob Cruso, international regional sales manager for Rhode Island-based New Nycon Inc., a company that distributes an assortment of fibers for concrete reinforcement, says not only do PVA fibers make for a stronger concrete, but the finished product has increased ductility, another big plus. “PVA fibers allow concrete to move or be more ductile and to absorb more energy, which eliminates cracking that may occur over time,” he points out.

Costwise, Cruso continues, a finished piece is very comparative to those made with GFRC. “You’ll use about half as much with PVA.” He estimates the cost to be about 5 percent to 6 percent of the total cost of the project. “And the material has a lot more benefits than wire mesh or steel reinforcement in precast countertops or architectural panels.”

In precast applications, the panels can be cast thinner, thereby reducing the amount of material used and the weight of the precast piece, he says.

Finally, Cruso maintains PVA fibers are easier to work with than GFRC because they are shorter. They measure 3/8 inch, compared to GFRC’s premix fibers that are anywhere from 1/2 inch to 1 inch long.

Tips for best results

The key to success with PVA lies in having the proper equipment, Cruso says – first and foremost, the contractor needs a mixer that has shearing action.

To achieve the best results with PVA fibers, Cruso cautions contractors to make sure the fibers are thoroughly mixed and homogenously dispersed throughout the mortar or concrete. He recommends adding the cement, sand, aggregate and water into the mixer for 3 to 4 minutes before adding the fibers, then mixing a few minutes more.

Schuler agrees with Cruso. He says adding the PVA fibers early with all dry ingredients is where you’ll get in trouble with the “balling” effect. He says he adds his fibers at the last 3 to 4 minutes of the mix cycle, when the mix is fully wet.

GST’s Glessner offers one more important opinion: Concrete laden with PVA fiber is not trowelable. “It’s such an aggressive fiber you can’t overwork it,” he says. After one or two passes, the whole thing will start to pull up. “This is an expert-use product,” he states. “It’s not for laymen.

“The product needs to be worked slowly,” he continues. “When it comes to precast, that’s not going to be a problem. But when you are doing an overlay, you can’t put a Magic Trowel down and move it back and forth. It’s really hard to work with. I just can’t explain how bloody hard it is to work with.”

Schuler says he really doesn’t have a problem troweling his PVA mixture but agrees it takes a certain bit of finesse to learn how to trowel it properly. “If you are using low water-cement ratios and higher PVA fiber loads, I recommend you don’t follow conventional troweling techniques. That’s a mistake some guys make. You need to wait for it to slightly set, then use water or lubricant, mag (trowel or float) quickly and then steel-trowel it to avoid the fibers pulling up.

“If we’re talking about the recommended lower dosage of 1 to 2 pounds a cubic yard,” he continues, “I don’t see how anybody would have too much trouble troweling it. It depends on your loading. You can have problems with any fiber if you load higher than you are used to.”

Still, once contractors get over the learning curve, Schuler encourages them to load up on the PVA. “A heavy dose has helped us get away from problems associated with placing primary reinforcement. PVA fibers are far easier to use than rebar and other wire tensile reinforcement. It’s helped us maintain our quality control.”

www.gst-intl.com

www.kuraray.co.jp/en/

www.nycon.com