Diamonds are an integral part of making concrete countertops — they’re used for rough grinding, shaping, honing and also polishing. However, there is a wide variety of diamond polishing pads on the market, and the concrete countertop contractor has little guidance as to which product will perform the best for his money.

It’s possible to find identical-looking pads that cost as little as $2 or as much as $100, so how can you tell what will give you good value and performance? Which is better wet or dry? And are thick polishing pads superior to thin ones?

Since concrete countertop makers grind, hone and polish concrete, it’s natural to look to two closely related industries for guidance: the polished concrete flooring industry and the granite countertop industry.

Polishing countertops vs. floors

Let us first look at the polished concrete flooring industry. Here diamonds are used in all aspects of refining a concrete floor to yield a mirror finish. Concrete floors are first ground and flattened, then progressively honed to remove scratches, and finally polished to achieve a smooth, glossy surface. This sequence can also be done on concrete countertops, so it’s natural to use the same grits of diamonds as are used with floors.

However there are several key differences that separate the polished concrete flooring industry from concrete countertops, and these differences are important to choosing the right diamond products for processing concrete countertops.

The first key difference is the concrete. With polished concrete floors, the concrete is nearly always several weeks, months or even years old, which means the concrete has had time to cure and gain strength.

Another difference is that the polishing contractor usually isn’t the one who has poured the concrete, so the concrete’s makeup, its strength and other characteristics aren’t often known. Good polishing contractors perform hardness tests to match their diamonds to the concrete so they get the best results.

And finally, the machines that do the polishing are very different. Floor machines are big and heavy, with large polishing heads that use diamond tooling that comes in different shapes, including blocks, plugs, segments or discs. Each machine manufacturer has brand-specific tooling carefully designed to work with their machines. Tooling design and grit sequence are chosen by the manufacturer to provide optimum performance and results. The bottom line is that when polishing a floor, all you have to do is follow the manufacturer’s instructions for diamond selection and you’ll get good results.

Unlike floor polishing, the concrete countertop maker doesn’t have the luxury of working with or waiting for fully-cured concrete, so finding the right tooling and knowing when to use it is paramount to producing a high-quality surface.

Polishing concrete vs. granite

The other industry close to concrete countertops is the granite industry. Here there are many similarities, not only with the tooling but with what is done to the material.

Processing concrete countertops generally means using a hand-held polisher to grind, hone and polish the surface of the concrete. With granite it’s no different, and in fact many of the electric and air polishers are shared by both industries.

The main difference between granite and concrete lies in the physical makeup of these materials. While there are very many different types of stone that fall under the commercial term “granite,” they all are more similar to each other than they are to concrete.

Granite is a solid slab of stone made up of tightly knit mineral grains. These grains are mostly quartz and feldspar, two minerals that are very hard. In fact, quartz is 70 percent as hard as diamond, and both quartz and feldspar are harder than steel. So the diamond tooling designed for granite has to deal with efficiently wearing away a very hard, solid material. Additionally, most granite fabricators need to polish only the edges of cut slabs, since the surface of the slabs comes pre-polished from the quarry.

Concrete is very different. It is a nonuniform material made up of harder aggregates bound together by a softer cement matrix. The aggregates vary in size, shape, surface roughness, hardness and mineralogy. The cement matrix varies from mix to mix, and more importantly, its properties vary day by day, since most concrete is very young and still gaining strength when it is being ground and polished.

When to polish

The challenge faced by all concrete countertop manufacturers is to be able to produce a smooth, scratch-free surface (polished or not) as soon as possible after casting.

Once the concrete has gained enough strength, the cement paste is strong enough to keep the aggregates from tearing out and also hard enough to be cut smoothly without eroding. Concrete cuts evenly and responds more like solid stone only when it is hard and strong enough. A sure sign of this is when the aggregate and the cement paste are cut smooth and flush with each other during processing.

Usually it takes about two days of curing for most concrete used in countertops to be strong enough to grind without damaging the pad or the concrete. It often takes more than four to five days for the concrete to become hard enough to begin the polishing process.

If concrete is processed too soon, the cement paste is too soft and too weak to bind the aggregates. Diamonds grab and tear the small sand grains out of the paste, causing them to tumble between the concrete surface and the diamond pad. This quickly chews up the concrete, leaving a rough and uneven surface, and it rapidly wears away the diamond pad. Even the best diamond pads will wear away far more rapidly than they should if the concrete is too young and too soft for processing.

Choosing your pad

What makes a good polishing pad for concrete?

There are many different sources, names, styles and prices for diamond pads on the market. This can be very confusing, and what often happens is selection comes down to price. This is unfortunate, because in many cases a cheap pad will cost you more in the long run.

Shopping by price may be tempting, since so many diamond pads look alike and all are described similarly, often being sold “for granite, engineered stone and concrete.” However, choosing the right pad matters, especially if you want the pad to cut well, last long and not cost a fortune.

Diamond quality

Diamonds are the expensive part of the pad, so it’s fair to gauge quality with price. However there are some very expensive pads designed for polishing stone that would be a waste on concrete, simply because concrete isn’t the same as stone and the benefits from buying and using such an expensive pad would never be realized.

The industrial diamonds used in polishing pads and in other diamond tooling (such as turbo cup wheels and profile wheels) come in different grades and grits, just like sandpaper. For example, a 200-grit pad uses smaller diamonds than a 50-grit pad, so it makes smaller scratches and produces a smoother surface.

However, not all 200-grit pads are the same. Cheap pads may have some diamonds in them that are a 200-grit size, but most of the diamonds may be much smaller. Even worse, there may be a handful of larger diamonds that got by due to poor quality control. So the bulk of the diamonds in the pad are too fine to cut like a 200-grit pad should, and the few larger diamonds will scratch and gouge the surface.

High-quality diamond pads use carefully graded diamonds that are all nearly the same size, and the density of the diamonds in the pad is higher too. This results in faster cutting and better surface quality, making the more expensive pad a better value.

The binder

The binder that encapsulates the diamonds is just as important as the diamonds, and it has a profound effect on the performance and longevity of the pad. Binder materials range from metal to ceramic to resin, and different materials are used for specific applications. Binder hardness matters too — a binder that’s too soft will wear away quickly when processing an abrasive material like concrete.

Metal binders are generally reserved for highly abrasive cup wheels, in which very coarse diamonds need a hard-wearing matrix to bind them. Metal-bond cup wheels are thick, rigid and designed for aggressive and rapid material removal. These usually don’t have grit numbers but are similar to a 15- to 30-grit equivalent.

Cup wheels designed for grinding granite and hard stones generally have a softer metal matrix. Hard stone calls for a softer matrix so new diamonds are continually exposed as the matrix wears away. A hard matrix wouldn’t wear away fast enough, and the cup wheel would glaze over.

Opposite to this are cup wheels designed for limestone, marble and concrete. In these tools the matrix is harder. Soft concrete is very abrasive, and this requires a harder matrix with a slower wear rate that extends the life of the tool without affecting cutting performance. Using a soft matrix tool on softer (often very young) concrete will shorten tool life.

Nearly all wet polishing pads use a resin binder, and here too resins vary. It’s very rare that a pad distributor will describe the pad makeup with any meaningful detail, so here personal observations and reliance on trusted recommendations are necessary to make a good choice.

Too often the least expensive pads use soft resin binders that wear away quickly. If you end up using three times as many pads as you would with a pad that costs twice as much, you are not saving money in the end.

Ceramic binders tend to wear better and stand up to higher temperatures than resin pads. Many dry pads use a ceramic binder, which helps to prevent the smearing and glazing that can occur when a resin-based dry pad is run at a speed that’s too high.

Size matters

Larger-diameter pads (such as 7-inch) are much more stable on large, flat areas than smaller-diameter pads (3-inch and 4-inch). However, larger pads become unstable on narrow sections of concrete.

A 7-inch diameter pad won’t stay flat or cut evenly on a 3-inch-wide strip of concrete. They are also difficult to use on the vertical edges of countertops. Only larger, more powerful polishers can use 7-inch pads. Most electric and all air polishers are lighter-duty, best suited for 4-inch and 5-inch pads.

Small-diameter pads are less stable and more likely to gouge when processing large areas on a big polisher, but with a smaller polisher (especially a pneumatic polisher) they work very well for processing edges and narrow sections.

A good all-around size is a 5-inch diameter pad. Many low-cost polisher package deals come with 4-inch pads. These can be difficult to control with hand-held polishers on concrete. Smaller 4-inch pads are really meant for use on hard stone, which is much less prone to gouging than concrete.

Thickness matters too

Diamond pads come in a variety of thicknesses, from around 2 millimeters to 8 millimeters thick.

Thicker pads will last longer, but thicker pads are stiffer and commonly prone to cupping when they dry out. Cupped pads don’t wear evenly, and often the outer area of the pad doesn’t actually make contact with the concrete, so although you are paying for a 7-inch pad, it’s wearing like a 5-inch pad.

Thin pads don’t last as long as thick pads (especially when aggressively cutting), but they are more flexible. This is a big advantage when honing or polishing inside curved integral sinks. Thin pads are easier to keep flat with a rigid backer pad. Thin pads are the most versatile when matched with the right backer.

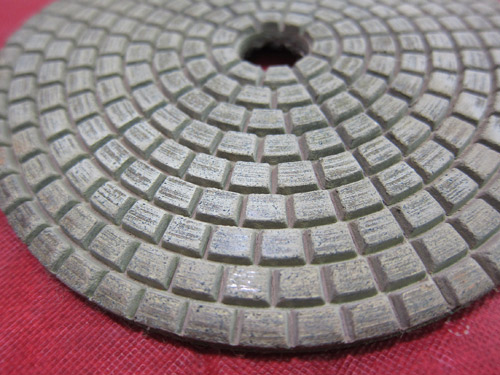

The pattern

The pattern molded into the cutting surface plays a role in the life span and the cutting quality.

Generally pads used for coarse honing (30 and 50 grit) should have an open pattern with wide and deep channels. Pads with open channels allow the abrasive cutting residue to be ejected quickly and effectively. This greatly increases the life span of the pad when aggressive stock removal is performed.

Pads with many narrow channels are best suited for polishing. Narrow channels clog more readily when aggressive cutting is performed and when insufficient water flows out from under the disc, but polishing (using grits 400 through 3,000) only generates small amounts of cuttings, so clogging is not an issue when polishing. Some well-made pads that have large open channels can also be used for polishing.

As you can see, there are many factors to consider in choosing a diamond pad. Start with assessing what you plan on doing with it.

- Are you using it for heavy stock removal?

- Is it for general honing?

- Are you polishing the concrete to a high gloss?

Then consider the variables I’ve outlined to make your choice. Only then should you look at price.

Using the right diamond pads for the job will make it faster and easier for you to create a high-quality finish for your concrete countertops.