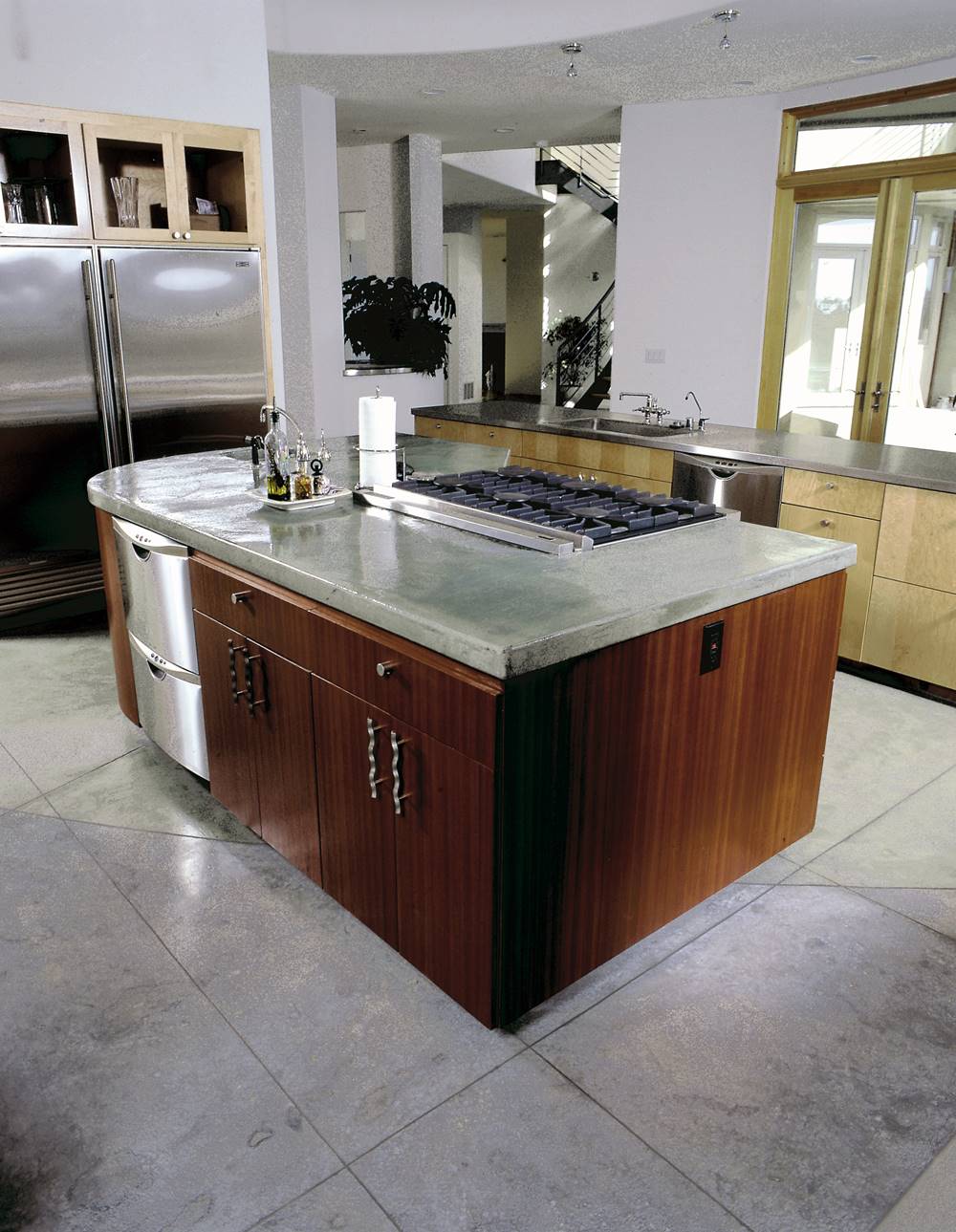

Handcrafted and distinctly unique, concrete countertops are finding their way into more and more homes and commercial venues. The versatility of the medium, as well as its unpredictability, is part of the attraction. It’s a growing trend and proving to be a boon to concrete artists. Here are some secrets to successful concrete countertops.

Jeffrey Girard, owner of FormWorks L.L.C. in Cary, North Carolina, says, “The number one feature of concrete countertops is that they are completely customizable — any shape, size, thickness, embedded items. If a client wants cobalt blue, I can give it to them. If they want something that looks like a beach with seashells and beach glass, I can do it.”

“Concrete can give a real ‘Old World’ feel,” observes Tom Ralston, owner of Tom Ralston Concrete in Santa Cruz, California. “It’s one of the most unique surfaces in that no one else will have exactly the same thing.” Ralston has embedded seashells, exposed the aggregate, hand troweled a finish, polished the surface, and sand- and glass-blasted the surface, all to achieve different effects.

Stuart Zumpfe, president of Concrete Effects Inc. in Langhorne, Pennsylvania, has impressed real ivy leaves, used traditional stamping skins, and embedded coins and custom tiles into countertop surfaces for distinct results. On one job, he reports, he sprinkled titanium dioxide on the surface before sealing to achieve a gold-flecked look.

Various contractors also use integral color, acid stains, color hardeners and micro-toppings. There is virtually no limit to what you can create.

Want to know a secret?

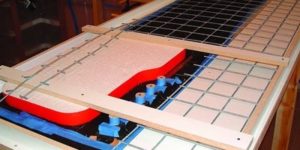

Mix designs, construction techniques and surface treatments vary from one concrete countertop fabricator to another, and many closely guard their proprietary methods as trade secrets. But for those curious to learn more about crafting concrete countertops, there are some basics. For example, concrete countertops are either cast-in-place or pre-cast and installation takes place after curing. Advocates for each method cite various benefits.

Dave Pettigrew, owner of Diamond D Company in Watsonville, California, pours concrete countertops in place. “I like to pour-in-place because I can form the countertop to anyone’s particular needs — radius edges, curved corners.” Because he pours the countertops in-place, Pettigrew says he doesn’t pour with joints. “We put plastic over the cabinets, we pour one-and-a-half inch thick, and we tell the customer we have to have control of it for 10 days.” Having control for proper curing is important.

“Sometimes form-setting on finished cabinetry is challenging,” reports Ralston, who also pours in-place. He also says “working within the framework of people’s schedules — scheduling with the cabinet installer, plumber, electrician, and dry-wall installer — especially on a remodeling project, can be tricky.”

Zumpfe pours in-place and borrows a trick from pool installers for nice rounded edges, he uses coping profile form liners.

If you want control, however, pre-cast is probably the way to go. When you pre-cast “you can control everything about the structure — the environment, temperature, curing time and how it cures,” explains Karen Smith, sales and marketing director for Countercast Designs Inc. outside of Vancouver, British Columbia. Another upside to pre-casting is that you can incorporate integral sinks into the countertop. “You can’t do that when you pour-in-place,” she says, “because [when you pre-cast] everything can be accessed from all sides.”

Allow for manufacturing time

Manufacturing time for pre-cast countertops can run six to seven weeks, but is generally five weeks, according to Smith. Forming and templating time takes about a week. Curing takes four weeks. Seams in pre-cast countertops can become part of the design. Generally, they use a silicon or latex caulk.

Girard, who is also a professional civil engineer, says the quality of the final product depends on how well the concrete is mixed, poured and cured. He advises, “Most concrete is used for structural applications. Countertops are structural and need to be approached that way.”

Another advantage to pre-cast is the ability to ship product to faraway locations, though shipping costs can be a limiting factor.

As Pettigrew points out, quantity may be the deciding factor for many contractors. “We do maybe three or four concrete countertops a month, so we pour-in-place. If I did 25 a month, I might pre-cast.”

Mum’s the word

Concrete countertop manufacturers — pour-in-place and pre-cast alike — obtain their materials from standard sources, such as concrete suppliers, ready-mix producers and stucco suppliers. Most contractors, however, do not share exactly what goes into the individual mixes.

For most contractors there was a good deal of painstaking experimentation before the “ideal” concrete countertop mix design was achieved. With such an intense learning curve, one can easily forgive the hesitancy to share. “You don’t get to practice much,” says Pettigrew. “Once we got the basics down, then we began refining it.” Pettigrew generally has a ready mix plant prepare his concrete according to his specifications, but, if the job is a small one, he’ll mix the batch himself right on the site. His topping mud is also a secret. “It’s my ‘secret sauce,’” he says.

Additives might include polymers and plasticizers. Ralston sticks with half-inch angular rock aggregate and pours as stiff a mix as he can

Typically, contractors use more than one material for reinforcement. Zumpfe says he uses fiberglass in his mix for strength and to reduce shrinkage. In the form he often uses vinyl-coated wire shelving, which he places upside-down, or welded wire. Ralston uses stealth fiber mesh (like little strings) and fibrillated fiber mesh (like netting). Sometimes, around sinks for drainage or next to stovetops as hot pot rests, contractors will partially embed metal bars — stainless steel, brass or bronze.

You could say every concrete countertop is made from custom-made concrete and you wouldn’t be wrong. Smith observes, “Everyone uses different things and most [contractors/manufacturers] keep their method under wraps.”

My lips are sealed

No less important than any other step is the sealer. “The sealer sustains the countertop, makes it still great looking in five to 10 years. That’s what separates the men from the boys,” admonishes Smith, who’s firm uses a water-based, USDA-approved sealer that is absorbed into the pores of the concrete. “It doesn’t leave a [visible] coating, so the surface looks and feels like stone,” she explains.

Ralston says different sealers give you different looks. “Acrylic waxes have a matted appearance. Silicon-impregnated sealers look natural. Polyurethane epoxies have a high gloss.” Which sealer he uses depends on what the client wants.

In kitchen situations, a sealer that is compatible with food use is desirable. Tim Sherry, northeast regional sales manager for Increte Systems, says Increte’s Counter Kote is an FDA-approved epoxy, designed to go on thick. He says Increte’s Dura-gloss, also FDA-approved and originally designed for use on floors, is a thinner water-based epoxy that also works well on countertops. Bomanite’s Florthane is an FDA-approved, highly chemical-resistant urethane sealer. Chris Stewart, Bomanite’s director of technical services, says Florthane is available in water-borne and solvent-borne formulas. Seal Hard, by L&M Construction Chemicals in Omaha, Nebraska, is a USDA-approved hardener/densifier. Stu Wood, chemist at L&M, explains that Seal Hard penetrates the surface of the concrete and, through a chemical ion-exchange, bonds with the concrete, plugging up pores and crevices.

The secret is out!

Concrete countertops are popping up everywhere, in residences, restaurants and commercial businesses. While the materials are inexpensive, concrete countertops are cost-competitive with high-end solid surface products and some natural stone products, such as granite, because of all the skill and labor that goes into creating them — figure $65 to $125 per square foot.

“For someone who wanted to get into making them, experimentation is the first step, but you have to know what you’re doing,” cautions Girard. “It’s too easy to make a concrete countertop — it’s difficult to make a good one. Durability depends on who makes them. The more experienced the fabricator, the better.”

The well-known durability of concrete notwithstanding, concrete countertops can crack and become damaged. Dropping a cast iron pot may cause chipping or break an edge. However, such an event is likely to damage other countertop materials, as well. Heat, abrasives, sharp knives, the strong colors and acid or base properties of foods are all a concern, but more for the sealer than the concrete.

As Smith observes, with repairs “you’ll never completely match 101 percent, it may be slightly different, but you’re not dealing with something that needs to be computer-matched.” Variations in coloration and embedded objects help hide stains. Zumpfe points out if you use a high-build epoxy resin sealer, scratches and wear marks can be sanded and recoated. Or, as with other classic materials — good leather, wood or natural stone — imperfections add character.

“One of the most challenging things about working on a concrete countertop is that it’s like working on a piece of furniture,” Ralston reflects. “Everything is brought up to your focal point and it’s constantly under scrutiny. You almost need an artisan to do this work.” Indeed. That appears to be the biggest secret of all.