If there is one product family in which a noticeable difference exists between competing products, it has to be the decorative overlay market. Gone are the days where a scoop of cement and bag of sand are mixed with diluted “milk” (slang for liquid polymer). While these basic recipes filled a need in the early days, the industry as a whole has grown up and become more technologically advanced. The variations in application as well as performance range from excellent to mediocre.

Recently I took part in a research and development program to produce some new hybrid overlays. I was able to look at popular products on the market, reverse-engineer them and see what makes them work. It was an interesting exercise that gave me a new appreciation for the complexity of decorative overlays and how they work. One big thing to come out of my research was the importance of a good blend of cements, aggregates and additives, but more critical was the role of the polymer.

Decorative overlays, with rare exceptions, fall into the product family known as “polymer-modified toppings.” A polymer is a long molecule made up of repeating structural units. These can be both natural and synthetic. In the case of decorative overlays, we are dealing with synthetic plastic-based polymers. To simplify what can be a complex chemical jungle, we just need to consider polymers used in overlays as “glue” that provides adhesion within the overlay as well as adhesion between the overlay and the substrate.

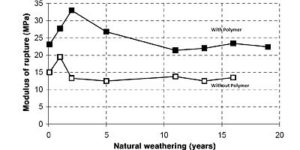

This glue allows overlays (toppings) to go down thin and still stand up to high levels of traffic and harsh environmental conditions. The industry standard requires regular concrete to go down at a minimum of 2 inches thick. Typical decorative overlay applications range in thickness from 1/32 inch to 1/2 inch thick, which is 25 percent to 65 percent thinner than concrete.

We all (should) know that the large aggregate bound by the cement paste is what gives concrete its strength properties. Since overlays are so thin, they do not have any large aggregate. This is where the polymer comes into play, giving strength to a thin cement-based product — in essence, replacing the larger stone.

There are two common polymer types used by most decorative overlay manufacturers: ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) and acrylic.

EVA is actually a blend of ethylene acetate and vinyl acetate. Not surprisingly, vinyl acetate’s most recognized application is as the main ingredient in Elmer’s glue and wood glue. Ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) comes in both dry powder and liquid emulsion form. This means EVA-based overlay systems can be “wet” or “dry.” A wet system is when the polymer is in liquid form, mixed with the powder at the job site. A dry system is when the polymer is a dry additive premixed into the powder and the whole system is activated by adding water.

I always compare EVA to the vinyl booth seats at the local diner when I was growing up. They were bouncy and stretched as I jumped on them, but never tore or ripped. Vinyl is what gives EVA the properties that are so beneficial to both cement-based microtoppings and stampable overlays. It makes the cement-based overlay more plastic, flexible and durable, not to mention sticky — like glue. It also gives the overlay a more synthetic, rubbery look, which may not be to everyone’s liking.

EVA-based overlay systems make great toppings for projects when protection from freeze-thaw, chemicals, or everyday soils and contamination is important. EVA is the most common form of polymer used in decorative overlays based on its cost-to-performance ratio. If the liquid polymer you happen to use as part of your overlay system smells like the white glue you used in grade school, then it’s a pretty good bet it’s EVA.

Acrylic polymer used in overlays is different than EVA in that it is only available in liquid form and has a much smaller market presence. It produces a much more rigid and hard-finished overlay product.

In my research I have found that acrylic polymers make for great microtopping overlays for interior applications. Acrylic polymers tend to produce overlay toppings that look and feel much like traditional concrete. You do not have the synthetic look and feel that sometimes comes with the EVA systems. Much like Plexiglas, which is clear acrylic in sheet form, acrylic-based overlay systems are rigid, durable and tough, but are not very flexible. This is why I don’t recommend them for projects where flexibility is important.

With all the focus on polymer types and properties, the dry side of decorative overlay systems can get minimized. It is important to note that having the right blend and type of aggregates is as important as having the right polymer. While the polymer is what gives the overlay most of its strength and adhesion properties, it will not make up for a poor mix design on the dry side.

The mix is more than sand and cement. In fact I found some popular overlay systems had no less than seven different dry ingredients, each one adding a nuance or performance characteristic specific to that system.

There are many brands of decorative overlay to choose from, each one unique. I encourage you to do your own research and ask lots of questions to discover if the brand or product you are using is best suited for your specific application. The polymers you use combined with the proper mix of dry ingredients makes products as diverse as the applications you use them for. Don’t settle for the one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to decorative overlays.