It pays to be part artist and part mad scientist when mastering the fickle nature of concrete.

Although it seems like a simple formula — cement, sand and water — every decorative concrete contractor knows it’s far from it. Decorative concrete mixes are often altered to lend the contractor some control over durability, efflorescence, its response to high or low temperatures and seemingly a million other factors. The problem is how altering the mix changes can be handled for various decorative techniques. What’s a contractor to do?

Let’s say you’re starting a large stamped concrete project. At first, the concrete is exactly the right consistency to accept a well-defined imprint. But as the project goes on, the concrete starts drying out.

“If you order a full truckload of concrete, that means all of it is ready to stamp at the same time, so you need to have enough people and enough stamps to be able to do it all within that window of time,” says Gabriel Ojeda, president of Fritz-Pak Corp. “Often, they’ll start at one end, and by the time they reach the opposite end, it’s too hard already.”

Or how about if you’re using dry-shake color hardeners on a patio deck? You know you need the concrete to be fairly wet to absorb and activate the colors. What if the temperature starts to rise, the moisture begins to evaporate, and suddenly the colors aren’t so colorful?

These common problems can be avoided with lots of testing. That’s where being a mad scientist comes in. But those contractors with a more artistic bent may also turn to the experience and scientific knowhow of manufacturers, who can help them eliminate some of the guesswork.

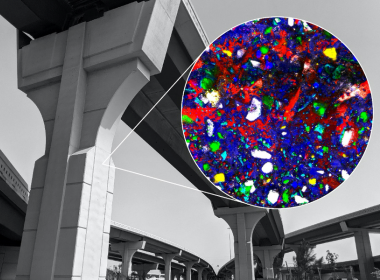

Contractors often turn to admixtures. These can include chemicals that reduce water content, speed or slow set time, or reduce shrinkage. Mineral admixtures include fly ash, slag and pigments.

Ojeda says trial and error is unavoidable. Know your products, he advises, understand how they’re going to work, and have a solution in mind if the unexpected occurs. “Contractors don’t do enough experimenting,” he says, “They do it on the job, and sometimes it works great, but sometimes it doesn’t.”

For example, in the summer, concrete dries quickly. In the winter, the opposite occurs. Ojeda says most people will simply work faster in the summer, “as opposed to saying, ‘Hey, we don’t have to rush everything, we can retard it and have plenty of time to finish the job properly.’”

He offers a solution to the contractor with the big stamped concrete job. Because workers have a small slice of time to make distinct impressions in the concrete, he advises placing half the concrete and adding a retarder to the second half, which buys time to work on the first half before the second half starts to set.

He offers a solution to the contractor with the big stamped concrete job. Because workers have a small slice of time to make distinct impressions in the concrete, he advises placing half the concrete and adding a retarder to the second half, which buys time to work on the first half before the second half starts to set.

Ojeda also has an answer for the contractor losing too much moisture to evaporation to allow for proper mixing of the dry-shake hardeners. He sells a “finishing aid,” which loosens up the top of the quick-drying concrete to make it more workable.

Another common problem, he says, is concrete that either flows too quickly or is too stiff. As with everything else involving concrete, getting it right is tricky. Adding water will increase flow, but it will weaken the concrete. Ojeda offers a superplasticizer that makes concrete flow without adding water.

Charles LeLand, director of training and product development for SureCrete Design Products, says reactive acid stains can present challenges. The higher the cement content, the higher the alkalinity, which acid stains need to react.

Overlay and topping mixes need to have the correct water content and level of permeability. A driveway overlay project can present problems if the weather is warm and the top is drying much faster than the bottom, LeLand says. An evaporative retarder will make the surface more plastic, allowing contractors more time to work with the product.

Minerals and salts migrating through an overlay can be a nightmare, he says. A product such as SureCrete’s Hydro Block can improve nearly any overlay by preventing efflorescence.

Minerals and salts migrating through an overlay can be a nightmare, he says. A product such as SureCrete’s Hydro Block can improve nearly any overlay by preventing efflorescence.

Creating high-performing concrete with consistent, rich color is particularly important in concrete countertops. B&J Colorants can produce any color on the Benjamin Moore color chart. Owner Murray Clarke offers detailed information on his Web site about how to add liquid pigment to a mixer, how to get complete dispersion of each ingredient, how much pigment to add and more.

Clarke says top-quality concrete, once created, can be sticky and difficult to work with, but there are ways to minimize the water content. He recommends Super Sealz, a dry white powder, at 10 percent of cement content for countertops. Super Sealz and Super Flowz will produce stronger, less permeable concrete and brighten the final cured concrete color. His Liquid Z admixture adds stain-proofing properties.

Not every contractor has the same commitment to high performance and zero loss of color. Clarke says he’s seen hundreds of poor exterior stamped-concrete projects, for example, where perhaps half the pigment was faded or washed out by rain.

Clarke says that most contractors want to concentrate on marketing their skills and not on mix-design details. “A lot of our customers like that we take the guesswork out.”

Test pours, experimentation, training classes, seminars and more testing can also help take the guesswork out. As Ojeda put it, “Concrete is cheap. What decorative concrete contractors are selling is their skill. The more skillful they are, the better off they will be with competitors.”