Decorative concrete dominates the company’s signature decorative concrete office, from a concrete chess table in a corner of the conference room to streams of color that stripe across the walls.

Decorative concrete dominates the company’s signature decorative concrete office, from a concrete chess table in a corner of the conference room to streams of color that stripe across the walls.

When newly minted college graduate Ken Froebigand a couple of his friends started their own construction company in the early 1970s, they took the name for their company from the then-trendy science fiction novel “Stranger In A Strange Land,” in which “water brothers” share a deep communal bond.

Froebig moved to Oregon and founded a new company in 1996, but his new company, like the old one, was called Water Brothers Construction. “The word ‘brothers’ was important to me to represent camaraderie and team spirit,” he says. “Water seemed appropriate to Oregon.”

Today, a deep communal bond is still at the core of how Water Brothers does business. But Froebig is in charge. When he started the Oregon company with a partner, they talked about turning it into a cooperative, he says, but that didn’t happen. He and his wife are the active owners of the business today. “I recognized early on that you need to have a leader, and that was me,” he says.

Today, a deep communal bond is still at the core of how Water Brothers does business. But Froebig is in charge. When he started the Oregon company with a partner, they talked about turning it into a cooperative, he says, but that didn’t happen. He and his wife are the active owners of the business today. “I recognized early on that you need to have a leader, and that was me,” he says.

With Froebig’s steady hand on the wheel, Water Brothers Construction never veers off course, even after its recent turn into the field of decorative concrete.

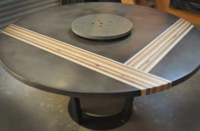

The company’s signature decorative concrete project to date has been for itself. Earlier this year, it moved into an 800-square-foot office on the ground floor of a mixed-use development in downtown Eugene. Decorative concrete dominates the space, from a concrete chess table in a corner of the conference room to streams of color that stripe across the walls.

The company’s signature decorative concrete project to date has been for itself. Earlier this year, it moved into an 800-square-foot office on the ground floor of a mixed-use development in downtown Eugene. Decorative concrete dominates the space, from a concrete chess table in a corner of the conference room to streams of color that stripe across the walls.

The conference table was poured in place, with gem fossils tapped into the surface. Grinding around the concrete edges of the gems to make the surface level exposed more aggregate than expected. But the visual impact looks literally explosive, with bits of stone fanning out around the gems on all sides. “Some of decorative concrete is luck,” notes Froebig. “I thought it came out pretty cool. I love this table.”

The table’s surface and the two desktop surfaces in the lobby are equipped with radiant heating. Froebig expects the heat from the three surfaces to keep the whole office warm in mild Oregon winters.

The table’s surface and the two desktop surfaces in the lobby are equipped with radiant heating. Froebig expects the heat from the three surfaces to keep the whole office warm in mild Oregon winters.

When the company was founded in Oregon, Water Brothers specialized in high wall foundations and hillside foundations, using an aluminum form system that Froebig says was unique to the area. Gradually, the company began taking on more specialized structural concrete jobs such as radius walls and caissons. It also constructed a concrete bunker for a 911 call-switch center.

The company first dabbled in decorative concrete three years ago, working with exposed aggregate, finishing walls and stamping patios. This year, the company has delved into decorative concrete much more extensively. The crew wanted the challenge, Froebig says. “As we evolved, the level of competency among our crew increased. The brothers were looking for something a little more creative.”

The crown jewel of one current project, at a home in the hills on the south side of Eugene, is a concrete garden shed with a waterfall cascading off the back part of its roof. A pipe pumps water to the top. “A lot of people want water features,” he says. “People like the sound of running water.”

The crown jewel of one current project, at a home in the hills on the south side of Eugene, is a concrete garden shed with a waterfall cascading off the back part of its roof. A pipe pumps water to the top. “A lot of people want water features,” he says. “People like the sound of running water.”

But even now, decorative concrete and hardscaping make up only about 20 percent of the company’s business. “Our bread and butter is still hillside foundations,” Froebig says. The company also maintains a small excavation business and does flatwork. Diversity is essential to the health of Water Brothers, Froebig says. “We’re not just a decorative concrete company. We still pride ourselves on being multifaceted. We do all phases of concrete. I don’t believe in putting all my eggs in one basket.”

Indeed, at the home with the water-accented garden shed, Water Brothers crews are also pouring the initial foundation, installing sand-finished walkways and doing prep work and flats. At a second current project, another Eugene hills home, the company is doing excavation, drainage, caps and detail work, building walls and stamping patios. “It’s a project perfectly suited for this company,” Froebig says.

Indeed, at the home with the water-accented garden shed, Water Brothers crews are also pouring the initial foundation, installing sand-finished walkways and doing prep work and flats. At a second current project, another Eugene hills home, the company is doing excavation, drainage, caps and detail work, building walls and stamping patios. “It’s a project perfectly suited for this company,” Froebig says.

His commitment to some parts of the business stems partly from pride. Foundation repair and replacement is not easy, he says, and Oregon’s historic bungalows can be saved with his expertise. “There are very few people who want to do that work,” he says.

In the Eugene market, decorative concrete projects have not generated enough revenue to sustain the company, he adds. People love his concrete countertops, but once they find out how much he charges, they walk away. “I find it really difficult to make money on those projects,” he says. “I’m not sure this market is ready.”

In the Eugene market, decorative concrete projects have not generated enough revenue to sustain the company, he adds. People love his concrete countertops, but once they find out how much he charges, they walk away. “I find it really difficult to make money on those projects,” he says. “I’m not sure this market is ready.”

The new office, anchored by its immobile poured-in-place table, is a public relations coup for the company. “We’ve got substance,” Froebig says. “We’re not going to disappear.” The downtown location offers visibility as well as proximity to downtown shops and eateries. “It’s important to come to work in an environment where you feel that you want to go to work,” he says.

Employee morale is important to Froebig. He says the key to keeping his business healthy is making everybody comfortable, both clients and employees. He hosts company parties and hands out colorful T-shirts emblazoned with slogans such as “Zen and the Art of Rebar” and “Foundations Keep You Grounded.” “Guys love this stuff,” Froebig says. “They just eat it up.”

Employee morale is important to Froebig. He says the key to keeping his business healthy is making everybody comfortable, both clients and employees. He hosts company parties and hands out colorful T-shirts emblazoned with slogans such as “Zen and the Art of Rebar” and “Foundations Keep You Grounded.” “Guys love this stuff,” Froebig says. “They just eat it up.”

Half of Water Brothers’ employees have been with the company for more than five years. When turnover does occur, Froebig doesn’t have to worry much about finding quality replacements. “They find us, usually through another crew member.”

At the same time, Froebig keeps a tight lid on the head count. Water Brothers once had 28 employees, and he says he wasn’t able to effectively manage employee attitudes and other intangibles. “Once it gets too big, you lose that brotherhood.”

At the same time, Froebig keeps a tight lid on the head count. Water Brothers once had 28 employees, and he says he wasn’t able to effectively manage employee attitudes and other intangibles. “Once it gets too big, you lose that brotherhood.”

Now, the company has 20 employees, including its president, and that’s the way he wants it to stay. “Right now, I want to be in five years exactly where I am now, but refined. I want the machine to work better.”