I received a call a little while back from an architect and general contractor named Graham Simmons. Graham had been referred to me by Jim Duvall, a concrete contractor who specializes in difficult lots, basements and foundations in the Berkeley Hills of California. Jim places and finishes the mud, and we sometimes follow and provide applied finishes: patina stains, dye washes, etc.

Graham and Jim were on a design-build project together – a really unusual garage addition to a Berkeley home owned by a husband and wife, two doctors, at the top of Buena Vista Way in the hills.

This was a small 400-square-foot garage with a twist. It was to house a really hot Ferrari, a collector’s item and an automotive jewel in anyone’s crown. Here’s the twist: Driveway access to the garage was a bit sketchy, so Graham had designed, and Jim was placing, a structural slab that would support a stainless steel turntable. This turntable would act kind of like a railroad roundhouse, enabling the driver to pull in and out without having to use the mirrors and back up. It would be surrounded by a thin-topping slab to potentially be finished in some exotic fashion (my job).

Graham had been calling me repeatedly about finishing the slab for maybe a couple of weeks, and we just weren’t able to link up. Scheduling conflicts, and I felt really bad. I knew he had a production schedule to keep. Late Sunday afternoon or early evening would finally accommodate all parties (designer, contractors, owners). So a meeting was set for Sunday at 5 p.m.

Graham asked if I might be able to meet him at the bottom of Buena Vista Way instead of at the clients’ house at the top, as he had something else he thought I might also be interested in.

Maybeck and the Temple of Winds

5:10 p.m.: A lovely East Bay summer afternoon. Sun above, fog in the distance. At the corner of La Loma Avenue and Buena Vista Way, Graham and his dog are waiting patiently for me in the shadow of a eucalyptus. “Sorry, I’m late, what’s up?” Graham answers my question with a question: “Do you know Bernard Maybeck?”

I did. Maybeck designed the iconic Palace of Fine Arts in the Marina District of San Francisco, and he was a developer and prolific designer of homes in Berkeley. Most of them are concentrated on Buena Vista Way, between La Loma and the top of the hill. Graham and I stood at the base of an all-cast-in-place concrete, Maybeck-designed Pompeiian villa, the Lawson House, talking shop. We talked design. We talked construction. We talked concrete. And we learned about each other.

Graham had been raised in this neighborhood, and as a teen, he had partied, drank and whatever in about every other Maybeck house. He joined the trades, became a carpenter and ski bum, and pounded nails, brews and the slopes in California’s High Sierra. Then he returned to the University of California, Berkeley where he earned his degree in architecture.

I shared of myself and what I knew of Maybeck. (I used to speak on the concrete reconstruction of the Palace.) Maybeck, like me, was a stylistic chameleon. He was equally comfortable designing in the Mission and Mission Revival styles, or Gothic or Arts and Crafts styles, or incorporating Beaux-Arts classicism.

Graham and I strolled up the street and took a peek at two of Maybeck’s own homes – 2780 Buena Vista, where he and his wife, Annie, both died in the mid-1950s, and 2711, the “Sack House,” where they had lived previously. These are both examples of Maybeck as an innovative concretist. Check out the sculptural, battered, board-formed fireplace at 2780. And note the walls of burlap sacks, dipped in a washing machine filled with frothy cement paste (Bubblecrete, invented by Berkeley resident John A. Rice), and hung on steel strand and chicken wire strung between studs. This was an inexpensive and fireproof method of construction after the original structure had burned.

We visited the Temple of Wings, perhaps the most well-known and iconic of Maybeck-designed residences. This is also called the Boynton House, a home conceived as a Greco-Roman temple and built without walls. It’s simply a roof supported by 34 Corinthian columns upon a radiant-heated slab, all in concrete. A house where Florence Treadwell Boynton taught generations of dance students, and where her friend Isadora Duncan used young Judd Boynton as a prop in their impromptu productions, this early 20th-century experiment in Mediterranean, neoclassical (and sometimes naturist) living offered curtains in lieu of walls. When the winds blew and rain fell, you drew the shades. Alas, this was ultimately to prove a failed experiment, as Northern California was only a semi-Mediterranean climate. It took a few winters, but walls were added.

Judd Boynton was later to become a Berkeley builder and character worthy of notice. His self-built residence was of concrete, sited on a difficult lot at the top of the Buena Vista hill. It features a massive retaining wall topped by an exceptional cantilevered great-room slab. The site was precarious. The view from the great room was like that of the pilot of a dirigible cresting the ridge of the Berkeley Hills, heading out and over the Golden Gate Bridge.

The radiant-heated concrete came in handy as the site of Mr. Boynton’s reputed sensual group get-togethers — now that’s what I call sensory concrete! And this floor I have some personal experience with – not from swinging parties, but from patina-staining the floor while with L.M. Scofield Co., during a remodel in the’80s.

Hume Castle and Po’ Mike

Our final stop before the clients’ house was at Hume Castle, designed after a 13th-century Augustinian monastery in France. Graham thought this one was by Maybeck, but I later discovered it was by another Berkeley-based architect, John Hudson Thomas. I was particularly interested in the Castle as it was apparently built of simple, unornamented, precast concrete blocks of soil cement. (Soil cement is concrete composed of portland cement mixed with site-excavated soil for coarse and fine aggregates and pigmentation.) Believing that the structure should be of the hill rather than merely on it, the builders cast these blocks on-site. This was in the 1920s, about the same time that Frank Lloyd Wright was in Los Angeles, designing and building with his Mayan-inspired textile block system featuring deep ornamental relief.

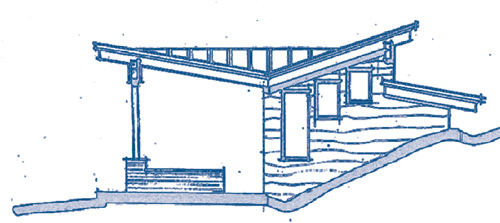

Hume Castle is a combination of both precast and cast-in-place soil cement. This is how I intend to build at The Po’ Mike El Rancho/Retreat, my isolated ranch in northeastern Nevada. I’m called Po’ Mike’cause I’m poor, but The Po’ Mike El Rancho/Retreat is sited in a valley along Indian Creek with an abundance of clay-free ancient alluvial deposits. In other words, I’m rich in soil, the kind that makes really good soil cement.