How is a puddle of water like a colored concrete slab?

“The color (of a puddle) is dependent on what is underneath it, suspended in it or reflected upon it,” says Steven Ochs, professor of art at Southern Arkansas University and owner of Arkansas-based Public Art Walks. The same holds true to concrete when it’s colored with transparent dyes and stains, he says.

A concrete slab’s base color largely determines the lightness and intensity of everything that follows. So, rather than starting with an all-gray substrate, you might try something different. “If you really want colors to be bold and bright, consider a lighter mix — or use the 14th-century Italian technique of ‘underpainting,’” Ochs says. “Just stain it white to start with. Then, the light will pass through the color and will illuminate upward through the layers of pigment and sealer to provide more intensity.”

The most practical reason Ochs can think of for decorative concrete contractors to try an underpainting technique is cost savings. “Some contractors have been using a white portland in order to get brighter colors once they stain,” he says. “They could use a standard mix, then stain it lighter before adding the final colors.”

The origin of underpainting dates back to 1,500 B.C. when Minoan artisans in Crete applied layers of plaster as a foundation for their wall paintings or murals. Eventually called fresco, this technique usually involved painting on moist plaster but not always.

In the years that followed, frescos spread to Egypt and beyond. “Frescoes could be found in ancient palaces, temples and even pyramids,” says Ralph Larmann, associate professor of art at the University of Evansville in Indiana.

The technique continued to evolve during the Renaissance, where artists created paintings in a series of layers, with each layer a different color. In the end, some of each layer would show through, creating a depth to the painting that a single layer of color couldn’t achieve.

The most popular type of underpainting today is a grisaille, a monochromatic picture or geometric design that often resembles a black-and-white photograph and usually involves shades of gray. “This involves a methodical process where the artist thinks about darks and lights first,” Larmann says. “The color would come later.”

One of the mains reasons an artist would use this process is to create a guide for the future layers of the painting, he says. “By using an underpainting technique, you’re less likely to have to fix a mistake because you would have already worked out the problem. If you know you have multiple layers, you can experiment a bit and make the design better. Even Michelangelo didn’t get everything perfect the first time through.”

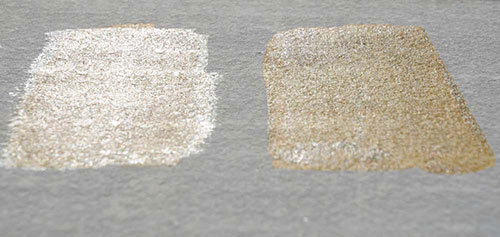

Ochs, who has painted a number of images on concrete, says he uses underpainting principles for more than just getting colors to pop. If the finished product calls for a metallic, pearlescent or other specialty paint, he works on the initial value scheme and gets everything looking great in blacks, whites and grays before applying the topcoat.

“You don’t want to muddy up the specialty paints by adding color to them,” he says. “They need to stay pure.” When you apply them over a black and white design, “the surface color is crisp and clean, and you still have all the details and the 3-D effects of the shading of the image underneath. And the surface will shine.”

For the more adventurous and artistically inclined, underpainting also can include color on color. “A lot of contemporary artists like to use a bright color underpainting and layer lighter or contrasting colors over it, allowing bits and pieces of the underpainting to come through,” Larmann says, describing a process called “scumbling.”

“This process could definitely be applied to concrete work with great results,” especially on rough or textured surfaces, he says.