For thousands of years the permanence of concrete has made it an ideal construction and design medium. Architects, engineers and builders have relied on in for centuries. Even the word “concrete” is often used as an adjective to describe the reality, longevity and durability of everything from objects to ideas. Despite this long and proven track record, some of the latest design and repair trends in overlays, toppings and coatings have revealed a critical fail point in that permanence concept: inadequate surface preparation.

Adequate surface preparation is rarely as appealing as putting down that last coat of sealer and admiring a job well done. It receives little fanfare. It also rarely makes the cover of trade magazines. However, it’s the most important aspect of any project and can quickly undo the skilled hand of any artisan.

Due to its often dull and monotonous nature, surface prep is often neglected or overlooked. Most of the neglect comes from good installers who have a specific standard they follow for every job without ever completely understanding how or why. This leaves the broad variety of slabs and substrates treated the same, despite their differences, and many variables unanswered.

Ninety-nine percent of the bond failure issues I’ve inspected have either been poor or incomplete surface prep and consistency. Just like preparing for an exam, job interview or business meeting, good preparation is about knowing the answers before they are asked.

Read the substrate

With overlays and toppings, good preparation means reading the substrate, knowing the materials, identifying all possible variables and accounting for them one by one. Doing this effectively ahead of the installation will eliminate most, if not all, chances for failure.

The current industry environment is one of open communication and free information, with many of the pioneers that developed the installation processes for these materials. Their combined years of know-how and experience can be used to eliminate any and all surprises.

Proper surface prep should provide a clean, sound and open substrate that’s ready to receive a uniform coat of the desired topping.

Clean and sound

A clean and sound substrate is free of contamination, previously applied coatings and loose debris. Also, its cracks, spalls, voids and depressions have been addressed and repaired. Each of these repair subjects could be an article on its own. However, the basic principle is to provide a clean surface where the final topping can cure consistently and properly.

Most materials cure through a chemical reaction. The rate at which this occurs increases as the mass increases. This means that doing your repair, leveling and final finish in one coat will result in differential curing throughout due to the material’s varying thicknesses. Most, if not all these differences, will be visible as “shadows” in the final finish.

Surface profile

The major mechanisms for a long-lasting bond between existing concrete and an overlay are the overlay’s adhesive properties and the mechanical bonding properties between the two materials. By far, the most effective way to maximize the bond is to adequately profile the surface.

There are many methods professionals use to profile a concrete surface. The most common are mechanically abrading, blasting with abrasives, chemically etching and using high-impact mechanical methods achieved with tools such as jackhammers and concrete floor scabblers.

The preferred methods are mechanical abrasion and blasting. Chemical and high-impact methods increase the risk of microcracking and leave residual byproducts behind. Although the latter two methods have their place, it’s best to consider them as a last resort when either of the former two are available.

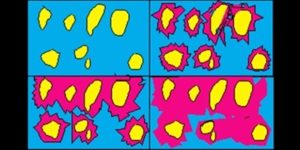

Effective profiling accomplishes two things. It increases the concrete’s effective surface area. It also opens and exposes pores and cavities in the concrete surface. Because of this, you may need more material to cover the now-enlarged and more porous surface.

What profile is right for the job?

Most materials require a profile that can be achieved through grinding or shot-blasting. However, some projects require more aggressive removal processes such as milling or scarifying. The profile left by these methods can typically require 20% or more material than that of a diamond-ground slab.

The process of exposing pores will have the greatest impact on primers, as well as materials applied without a primer. Because the density and porosity of concrete can vary broadly between different sections, you need to accurately measure each project’s profiled area to ensure you have enough material to cover the effective surface area.

One good analogy to describe the difference between effective surface area and geometric surface area is to compare Texas to Colorado. Looking at a map, it’s clear that Texas’ geometric surface area, in terms of square miles, is much greater than that of Colorado. Yet, if you were to flatten all of Colorado’s mountains and valleys it would have the same effective surface area as Texas.

When concrete is profiled, copious peaks and valleys are created along multiple planes and axes. This expands the overall interface area between the surface and the overlay. By definition, all bonding, and material properties that affect bonding, occur at this interface — so the bigger the better.

Exposing pores

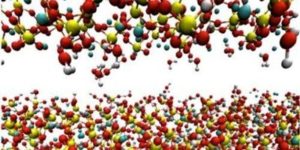

Concrete is an inherently porous material. Through the placement and finishing process, capillaries and voids are formed throughout the matrix as air is entrained, mix water migrates and water evaporates.

The final finishing stage closes off these capillaries at the concrete surface. Removing the surface layer exposes openings and pores beneath it, allowing overlays and coatings to firmly anchor to the existing concrete by working into the voids and curing into the substrate to form a monolithic structure.

Properly exposed pores create the environment necessary for the other factors that directly attribute to overall bond strength: the substrate’s moisture content and the overlay material’s physical attributes.

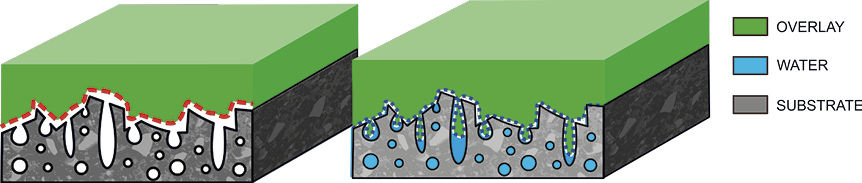

The diagram above illustrates how both overlay slump and substrate saturation can impact final bond. Although this example illustrates priming using only water, the physics remain constant for most overlays and coatings regardless of priming method.

Priming with water

When priming with water, the industry standard is “SSD.” This stands for Saturated, Surface Dry. This means that you saturate all the substrate pores and capillaries with water, but there’s no water on the surface. SSD prevents a “thirsty” floor from robbing the overlay material of needed hydration water. However, it doesn’t contribute any significant amount of water to the mix, effectively creating a moisture-neutral surface.

Due to their polarity, water molecules have the useful characteristic of connecting to each other via hydrogen bonds. When the water in a cementitious overlay comes into contact with the water within the substrate, these covalent bonds draw the mix water, along with cement and aggregates, into the pores creating a strong mechanical bond between the two.

If you haven’t saturated the overlay or the substrate adequately, then it creates a moisture differential in which water migrates away from where it needs it. This is why it calls for primers or slurry coats when you need low water-to-cement ratio overlays or patch materials.

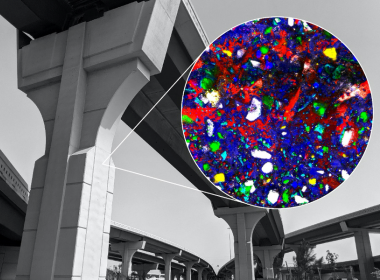

Identifying surface profiles

The final question to answer now becomes “what is the proper surface profile?” Most turn to the International Concrete Repair Institute for guidance. The ICRI focus is repair, but the first and most critical step of any repair is surface preparation.

To take the guessing game out of surface preparation, ICRI created the Concrete Surface Profile Chips. This are also known as ICRI CSP chips. These are a set of rubber plaques that have the numbers 1 through 10. They show properly prepared concrete, ranging from almost smooth to extremely rough.

The chips, along with the accompanying booklet, establish a third-party guideline for what properly prepared concrete should look like. It also establishes how to achieve the desired level of surface preparation. Additionally, it provides a guide for which profile is best for a particular overlay or coating system. The chips and guide have become a standard reference for manufacturers of most systems. They sell for $122 to ICRI members and $244 for nonmembers,

In conclusion

Overlays can present a daunting challenge to many contractors. This is because of a perceived liability or risk of failure that they present. But there are many installers that regularly use these materials with a very low failure rate. This is largely because they understand how all these pieces come together.

Successful overlaid surfaces aren’t works of art that require an extraordinary talent to execute. However, they do require a high degree of technical discipline. There is a basic outline to getting the best results. But. the key is identifying the project-specific variables and tailoring specific solutions to achieve the principles discussed here. Even high-performance, ultra-modified materials can’t replace the careful consideration and attention to detail required for proper surface preparation.