Picking the right power trowel for the job is something a decorative contractor needs to consider carefully.

A power trowel will save time and sweat, but the machine is not known for its delicacy. Between its weight and the heat of its steel blades, the wrong choice can wreak havoc on a decorative concrete floor. So do your homework.

Ride-on vs.walk-behind

Power trowels can be divided into two categories: walk-behind and ride-on.

The first consideration in picking one or the other will be the size of the job. A ride-on power trowel’s greatest strength is its productivity — it contains more blades and pans on its underside. Its greatest liability is its size. It is simply too big and heavy to maneuver into a residential basement and along the edges of walls. It also costs much more than a walk-behind.

The high productivity of the ride-on helps with the fast-curing concrete used in commercial applications. But the heavy machine would obliterate a thin overlay system.

So a decorative contractor, who is typically working a relatively small residential job, will probably be using a walk-behind power trowel. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a ride-on on something smaller than 2,500 square feet,” says Ed Varel, engineering project manager with Stone Construction Equipment Inc. “And ride-ons are such large-ticket items that the only way they pay for themselves is to use them quite a bit.”

A walk-behind power trowel handles like a waxer, Varel says. “The trowel is constantly trying to push you over. They are tough to operate. You have to find somebody willing to build up the calluses and muscles to operate that guy.”

Not all walk-behinds are created equal, of course. Weight is an issue here too. In some climates, even a walk-behind may be heavy enough to sink into green concrete. “In the cold North, you want it light, or otherwise it will dig into the finish,” Varel says. “Northerners want as little weight as possible, because things don’t set up real quickly. Down in Florida, they can’t get enough weight. They want the biggest.”

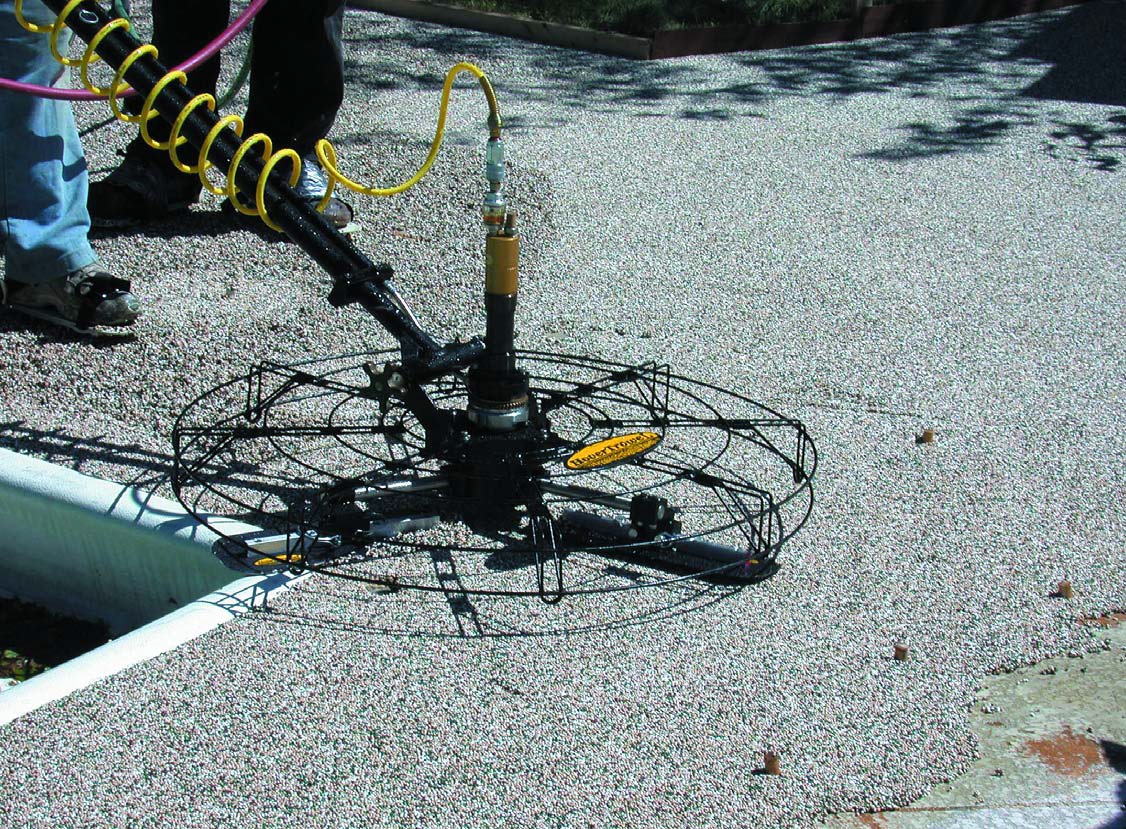

There are specialized power trowels that are designed for use on polymer-modified systems. For example, the HoverTrowel is lighter than a conventional walk-behind, which allows it to be operated on a thin-coat system that won’t take a heavier machine. “The HoverTrowel is really the only lightweight trowel on the market that can handle overlayments,” says HoverTrowel Inc. president Drew Fagley.

The HoverTrowel is pneumatic, which makes it a good choice in jobs where a gas-powered machine can’t be used. If a contractor wants to switch to a gas-powered engine, the HoverTrowel can be retrofitted with one.

“It’s a power trowel that also does things that a man can do,” Fagley says. “It’s sort of a hand trowel standing up.”

Varel’s company, Stone Construction Equipment, makes power trowels with unique features of their own. An RPM adjuster and hand-disconnect clutch allow the engine to rev up to speed before the blades are engaged. When the operator isn’t actively troweling, he or she simply disengages the blades. The engine continues to hum at the same RPM, ready to resume work at a second’s notice.

A safety switch on Stone’s machine disengages the blades automatically if the machine spins one full turn, safeguarding against the power trowel running amuck, injuring workers and ruining the pad.

Then there is the remote-control power trowel. White Cap Construction Supply exhibited a Tibroc CCF-40 radio-controlled power trowel at the 2005 World of Concrete conference. The 85-pound machine, which the company bills as the first of its kind, is controlled with two joysticks.

Remote-control power trowels aren’t in wide use right now, but they might catch on. They would reduce operator fatigue without being as big or expensive as a ride-on, Varel says. “They would be a little bit of both worlds, is what I’m thinking.”

Fagley also likes the idea. “I personally think down the road there is going to be a lot of remote troweling done,” he says.

Choosing a blade

After picking a machine, a contractor must decide what will go underneath it.

The blade “spider” of a power trowel extends from the center like the blades of a lawnmower. There are three categories of blades: float, finishing and combination.

The float blade is used first, spinning flat at a relatively low RPM rate. As it works over the surface, high spots are leveled, water rises to the top and larger rocks sink.

Then comes the finishing blade, applied with a higher RPM and at a slight angle. The heavier pressure seals the concrete and increases its density.

Combination blades can be used to both float and polish, as long as they are reset at the necessary angle between tasks.

Instead of float blades, an operator may attach paddle-shaped float pans to the spider. The attachments are often used to smooth epoxy coatings over concrete floors. They will also leave a flatter surface than float blades, given the same number of passes. But because pans don’t close up a surface as effectively as blades, they are not used for finishing.

Each type of blade is progressively narrower, with floats being the widest and finish blades the skinniest. Smaller, stiffer finish blades will produce a harder swiping action and better densify molecules in the concrete, says Jeff Snyder, sales manager with Wagman Metal Products Inc. “The hardest surface is going to be achieved by a finish-style blade.”

Wagman Metal Products makes several series of plastic trowel blades that should last as long as the steel variety. And unlike steel blades, plastic floats won’t leave burnish marks, an important consideration when power-troweling color hardener. “You can get a high-polish finish with plastic blades without burnish marks,” Snyder says. “You can spin plastic on a surface until the machine runs out of gas and not mark it.”

Other specialty attachments will go underneath too. Grinding blocks can be attached to rub out screed marks. Edger blades, with ends that are curved instead of square like traditional blades, can get right up against a wall.

The HoverTrowel takes mahogany or magnesium floats, which would tear apart a conventional trowel. This feature may come in handy when a contractor doesn’t want to use steel trowels because of their tendency to close the pores of the surface. Closed pores can lead to spalling in cold parts of the country where the concrete is subject to freeze-thaw cycles. “With mahogany, pores stay open and the concrete can breathe,” Fagley says.