The annual meeting of the American Society of Concrete Contractors, held in Denver in September, was a showplace of what can go wrong — by design. A popular workshop on decorative concrete, “What to Do When Things Go Wrong,” was followed in the afternoon with demonstrations of common problems and the products and techniques to correct them.

Presenters Bob Harris of the Decorative Concrete Institute and Clark Branum of Brickform Products reviewed several common problems — and solutions — with stamping, staining, overlays, integral color and concrete countertops. Some of their suggestions are reported here.

Stamping

Harris and Branum emphasized that the most effective way to deliver a stamped project that lives up to what the customer expects (and thus will pay for) is to make sure the customer knows what to expect. Harris said that in thousands of stamp jobs, he has only completed one that was “perfect,” and that was only three yards. Samples and mock-ups created with the exact mix, materials and sealers you plan to use will give customers the best idea of what their project will look like. Your mock-ups should use not only the same materials you plan to use on the job, but also the same techniques. A 2′ x 2′ sample that takes hours of painstaking work to prepare is not likely to convey an accurate idea of a finished project.

Once reasonable expectations are in place, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. One common problem with stamping is the concrete setting too fast, which results in poor imprints as well as cracks. Partnering with the ready-mix supplier and getting the mix just right are critical because the substitution of fly ash for cement (currently in short supply) or the addition of water reducers can ruin a stamping project. The speakers recommended identifying one’s own design mix with a code for the ready-mix supplier so it will be delivered exactly the same every time.

Plastic shrinkage and stress cracks are caused by moisture evaporating rapidly — faster than the bleed rate — from the surface. It’s best to solve this problem by applying an evaporation retarder over a dry shake color hardener, not by adding “water of convenience” to the surface.

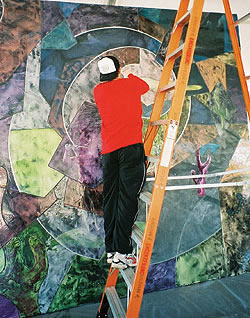

Clark Branum of Brickform Products removes blemishes, including pencil marks, from a stained slab during demonstrations at the ASCC annual meeting. The color was later restored by applying a matched water-based acrylic stain with an airless sprayer.

Common causes of concrete failing to take a chemical stain as expected include incorrect slab preparation, contaminants on the slab, the use of certain finishing techniques and mix design. Contaminants like old sealers, oils and food residue must be cleaned from the slab before stain is applied. If one part doesn’t take a stain, a matching water-based stain can be applied to that area and the edges feathered with an airbrush or stipple brush to blend in.

Timing is everything in a staining project. The fresher the slab, the more intense the color will be. Blue or green stains should be applied as late as possible to prevent them turning black.

Even if the stain is applied perfectly to a well-prepared slab, the project is still vulnerable. Make sure the trades that follow understand that the floor will be exposed and that driving a forklift over it, leaving a toolbox on it or writing out a quick calculation with a pencil will leave permanent marks. While Harris and Branum strongly recommend an exclusion in the contract making the general contractor responsible for this type of damage, some simple repair techniques can also help. Imperfections and light damage can be sanded away and a matching water-based stain applied to repair small areas.

Overlays

Poor bonding is the cause of most overlay failures, and failure to bond is usually caused by poor surface preparation. Old sealers must be removed and the surface neutralized.

Cracks and shrinkage occur when an overlay sets too fast. This happens when the substrate is too dry or when high temperatures, wind or sun accelerate the set. If possible, apply overlays during the cool part of the day when the surface is shaded. Also, priming the clean surface before applying the overlay prevents moisture loss into the substrate. The overlay needs to be applied in the correct thickness, and maintaining a heavy, “fat” wet edge prevents moisture loss and unsightly transitions.

Blistering is caused by improper priming, substrate conditions, air entrapment and overworking the overlay. This problem can be prevented by allowing the primer to tack up, keeping the substrate moist, avoiding overmixing, and using a resin float. Blisters can be reduced by running a spiked roller over the surface or by sanding them off.

Integral color

Compared with labor-intensive techniques like stamping and staining, integral color would seem pretty straightforward, but colored concrete can look blotchy and uneven when it suffers what Branum and Harris called “differential curing.” They made a plea to “stop mix abuse” — in other words, a consistent mix from batch to batch is critical. Some curing methods adversely affect integral color, so it’s essential to check recommendations from the color supplier. Problems will also occur if you have an uneven subgrade, which will cause variations in slab thickness. An uneven slab won’t cure uniformly, and the color may end up dappled.

Integrally colored concrete will also cure at different rates if objects are set on it. Avoid tossing used forms, setting toolboxes or storing construction materials on colored concrete before it is completely cured.

Sometimes these color differences will disappear with additional cure time. Other means of color correction include dissipating cures, color cures, color waxes, pigmented sealers, and water-based stains applied to the discolored area.

Poor finishing also impacts integral color. Bleed water on the surface, finishing too soon and overworking or burnishing the surface will all make the color uneven.

Countertops

Countertops create many of the same issues as other concrete projects, but on a smaller scale and often under closer scrutiny. When adding coloring agents or other ingredients to the mix it is important to remember one is working with relatively tiny amounts, so precise measurement is required to maintain consistency.

Countertop slabs are at risk for cracking and curling. Again, proper mix design and consistency help prevent such problems. Proper reinforcement also prevents problems. Flexural strength is more important than compressive strength for countertop mixes to prevent cracking, and structural steel reinforcement is one way to provide the strength a countertop requires without stressing and cracking the concrete.

As interest in decorative concrete grows, the risk of poorly installed projects — installed by inexperienced, untrained contractors — multiplies. The American Society of Concrete Contractors and the Decorative Concrete Council are working hard to promote quality and protect this booming industry.