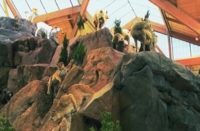

Richard Winget sees himself as a glorified copycat, an artisan who uses concrete and other mediums to simulate everything from cavern environments, majestic rockscapes and award-winning underwater reefs to rain forests, waterfalls and mountain landscapes.

The owner of Authentic Environments, in Huntington Beach, Calif., Winget has helped create water parks, zoos, hotels, casinos, aquariums and major theme parks all over the world. Before he founded Authentic Environments in 1994, he traveled as a freelance artist to exotic places including Taipei, Rio de Janeiro, St. Thomas and Hawaii and used his simulating skills on projects there.

“I have had the pleasure of working with, and learning from, some of the most creative minds in the industry,” he says, many of whom he has worked with time and time again because few can do what they do. The crews, he says, typically hail from all over the globe and become like family for the six to eight months they are on a job.

“I have had the pleasure of working with, and learning from, some of the most creative minds in the industry,” he says, many of whom he has worked with time and time again because few can do what they do. The crews, he says, typically hail from all over the globe and become like family for the six to eight months they are on a job.

Although he still accepts out-of-town commercial gigs from time to time — especially when it comes to zoos — Winget today mainly concentrates on custom residential projects closer to home in Los Angeles and Orange counties. Much of it consists of elaborate pools for celebrities or sports figures where the rockwork generally costs from $80,000 to $150,000 and takes somewhere between eight weeks and a few months to complete.

Learning the rocks

Winget first began learning the basics of rock formation and architectural concrete façades doing custom residential jobs in Phoenix, Ariz., while still in high school. When he graduated in 1986, he moved to Las Vegas where he spent two years as a union apprentice crafting the volcano at the Mirage casino on the strip. The GFRC project, he remembers, was the biggest project of its kind at the time.

Since then, the rock business has changed considerably. “What once was done with rebar benders is now done with AIM (auto industry machinery) or CNC (computer numeric controlled) wire-bending machines, CAD scans and chip technology,” he says. He cites examples of this type of fabrication that include the Expedition Everest ride in Disney’s Animal Kingdom in Florida and Disneyland’s Cars Land in California.

And even though due to budget constraints most contractors can’t always use the latest and greatest technology — Winget still bends rebar by hand in the field — he believes the next generation of scenic and theme workers should learn about the proper methods of operation and steps to follow.

Delving deeper

Winget’s techniques have seasoned since he started in the business. “I used to be all about the carving as a lot of up-and-comers are, but I soon realized that there is a lot going into this work and each step directly affects the next,” he says. “Throwing mud onto old tires, sand bags or Styrofoam is an unacceptable building practice!”

He urges those just breaking into the business to take training classes and seek out veterans who can teach contractors proper techniques. Practice techniques at the shop or in your garage before you do it for pay.

“Follow the large projects and see if you can get hired on,” he suggests.

“Take pictures of a rock or tree branch and try to recreate its texture and color. Be a problem-solver. Try new things. Always use several references — don’t guess at how something looks. Build yourself a library you can draw from,” he says. “Companies are willing to pay people who can simulate nature.”

The commercial architectural façade work he does, Winget says, differs from vertical decorative concrete in that the work is engineered according to detailed drawings and checked by inspectors to make sure standards are met. Although rules vary from state to state, with some having very lax standards or none at all for things such as boulders at the edge of a pool, Winget says he typically builds to meet California’s more stringent code. “I always follow California’s standard specifications at a minimum,” he says.

Simulated environments

Marrying the artistic trade to the traditional construction process can be difficult when the traditional contractor strives for a smooth-troweled surface free from imperfections and the artisan behind him wants to carve big cracks in it to simulate seismic activity to help tell the story, Winget says.

“Try explaining to a block wall contractor that he needs to purposely construct his wall in a crooked fashion so that we can make it look as if it is the only wall that has been left standing after an archeological excavation of an ancient city 1,000 years old,” he says. These are the types of challenges faced by those in the business of storytelling through simulated environments.

“Fooling people into believing what they are seeing is real is how we measure our success,” Winget says. But it doesn’t stop there. The concrete creations not only have to look real, they also must achieve what they were designed to do.

For instance, in a zoo exhibit some rocks are integrally heated to draw animals to them for comfort and are positioned close to the viewing window so visitors can get a good look at the animals. “Food caches” also bring the animals close to the viewing window. “The food caches are like a deep split in an artificial tree or a deep crack in the rockwork. The location is important and it has to be natural-looking,” Winget says.

“Waterfalls, ruins or artificial trees are used as focal points to bring interest, too. The idea is to showcase the animal while educating the public about them.”

Besides looking real and serving purposes for the animals and audiences, rockwork is also used to hide unsightly objects such as special effects equipment, plumbing, electrical, audio and HVAC components. At park entrances and queue lines, rockwork can block unwanted views, lay the groundwork for what’s about to come or serve as seating for the weary. For each of these uses, the rockwork must be fabricated to specifications.

Besides looking real and serving purposes for the animals and audiences, rockwork is also used to hide unsightly objects such as special effects equipment, plumbing, electrical, audio and HVAC components. At park entrances and queue lines, rockwork can block unwanted views, lay the groundwork for what’s about to come or serve as seating for the weary. For each of these uses, the rockwork must be fabricated to specifications.

Manufacturing and training

In addition to running a simulation construction company, Winget also produces a preblended sculptural concrete called Carve-Right that’s used in the scenic and theme industry to build trees, rocks and landscapes.

“It’s lighter than traditional cement and a little finer and stickier so it stays where you put it,” Winget says about the product he introduced in 2010. “We also engineered the lime out of the product, and that greatly reduces the efflorescence problem that has been plaguing us for years.”

About three years ago, Winget also began teaching classes where students can learn to build rockscapes and water features from the ground up. “You have to learn proper techniques and then develop speed to expedite the process,” he says. “And that’s what I teach them.”

He says he emphasizes the importance of personal protective equipment, such as gloves, safety glasses and work boots, and the proper way to lift heavy objects so students’ backs don’t give out at an early age. “I’m fortunate,” he says. “I have all my fingers and toes.”

Winget also produces training DVDs filmed by a professional crew based in Los Angeles. The DVDs, which run anywhere from two to four hours, are of his projects from start to finish. You can watch trailers on YouTube, he adds.

“I’ll never do anything different from building naturalistic environments or geological formations, because it’s too much fun,” Winget says. “The only thing I want to do is make it better.”

www.authenticenvironments.com

www.carve-right.com